I once approved a steel erection contractor because their paperwork was flawless. They had ISO 45001 certification, a pristine TRIR of 0.0, and a 200-page safety manual that looked like it was written by a legal scholar. Three weeks into the project, I stopped the job because I found their “certified” riggers using a frayed synthetic sling over a sharp beam edge, with no tagline, while the supervisor sat in his truck on the phone. They looked perfect on paper, but they were incompetent in the field.

That experience taught me that contractor selection is not an administrative box-ticking exercise; it is a risk management investigation. When you hire a contractor, you are not just buying labor; you are importing their culture, their habits, and their potential failures into your site. If they fail, the regulator doesn’t care that you “hired an expert”—they care that you failed to vet them. Below are the 16 critical factors I now use to separate professional partners from liability time bombs.

TL;DR

- Paperwork lies: A perfect safety manual means nothing if the crew on the ground can’t explain the hazards.

- Look for leading indicators: Incident rates (TRIR) tell you the past; reporting culture and observations tell you the future.

- The hidden risk is subcontracting: If your contractor hires a cheap sub, you inherit that risk. Always audit the chain.

- Financial health equals safety: If a contractor is desperate for cash, they will cut corners on PPE, maintenance, and supervision.

- Interview the Supervisors: Don’t just talk to the Sales Director. The site supervisor’s attitude determines if your project succeeds or fails.

The “Paper vs. Reality” Baseline

These factors separate the contractors who perform safely from those who just write about it.

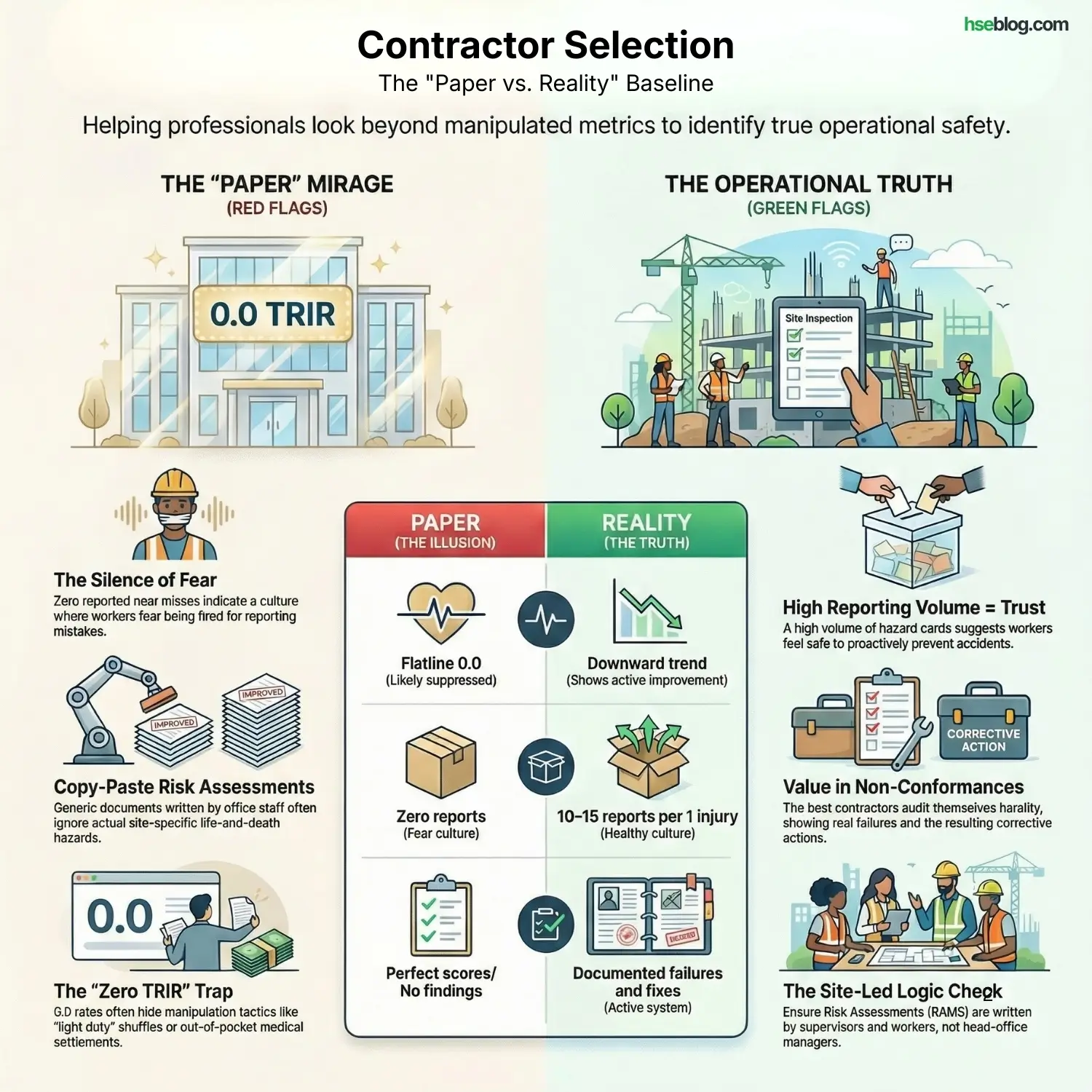

The “Paper vs. Reality” baseline is about stripping away the marketing to see the operational truth. You are looking for the gap between what they promise in the boardroom and what they deliver in the mud. Here is the detailed breakdown of how to scrutinize those five critical factors.

1. Lagging Indicators (TRIR / LTIR): The “Zero” Trap

The Total Recordable Incident Rate (TRIR) is the industry standard for measuring safety performance, but it is also the most manipulated metric in the world.

The Manipulation Game

I have seen contractors keep their TRIR at 0.0 using aggressive “case management” tactics that are technically legal but ethically bankrupt:

- The “Light Duty” Shuffle: A worker breaks their hand. Instead of sending them home (which creates a Lost Time Injury), the company creates a fake job for them in the office, “scanning documents” for six weeks. The LTI stays at zero, but the risk remains high.

- Cash Settlements: Some unethical contractors pay for medical treatment out-of-pocket rather than filing an insurance claim. This keeps the injury off the official “OSHA log” or insurance record.

How to Analyze It

When you look at their TRIR:

- Demand the OSHA 300 Logs (or equivalent): Don’t just look at the summary number. Look at the specific injuries listed. Are there a lot of “back strains” or “dust in eye” cases? This actually shows honesty.

- The “Too Good to Be True” Ratio: In heavy civil or oil & gas, a TRIR of 0.00 over 5 years is statistically improbable unless they have very low man-hours. If they claim 2 million man-hours with zero recordables, they are lying or they are not reporting.

- Trend Direction: I prefer a contractor who had a high rate three years ago but has steadily decreased it year-over-year. That shows improvement and management commitment. A flatline zero shows stagnation or suppression.

2. Leading Indicators & Reporting Culture: The Volume of Noise

Lagging indicators tell you who got hurt; leading indicators tell you who is about to get hurt.

Why “Zero Near Misses” is a Red Flag

If a contractor tells me, “We don’t have near misses because we are safe,” I end the meeting. In construction and heavy industry, hazards are constant. Equipment fails, weather changes, people make mistakes.

- Zero Reports = Fear Culture: It means workers are afraid they will be fired or yelled at if they report a mistake.

- High Volume = Trust: A stack of 500 “Hazard Observation Cards” means 500 times a worker stopped, looked, and fixed something. That is 500 accidents prevented.

What to Look For

Don’t just count the cards; read five random ones.

- Low Quality: “Worker wore PPE.” (This is just filling a quota).

- High Quality: “Noticed hydraulic hose chafing on the excavator arm. Stopped work, called mechanic, replaced hose before rupture.” (This is proactive risk management).

- The Ratio: A healthy site usually has a ratio of about 10-15 near misses/observations for every 1 recordable injury (Heinrich’s Pyramid concept). If the ratio is off, their culture is off.

3. Quality of Risk Assessments (RAMS / JSA): The Logic Check

The Risk Assessment and Method Statement (RAMS) or Job Safety Analysis (JSA) is the script for the work. If the script is bad, the movie will be a disaster.

The “Copy-Paste” Syndrome

I once received a RAMS for a project in the middle of the Saudi Arabian desert that listed “drowning” and “life vests” as control measures. The contractor had copy-pasted a RAMS from an offshore project and didn’t even read it.

- The Danger: If the RAMS is generic, the workers will ignore it. It becomes “tick-box” paperwork rather than a survival guide.

The Detail Test

Pick a specific high-risk activity relevant to your scope (e.g., “welding inside a tank”) and check their JSA for that specific line item.

- Generic (Fail): Hazard: Fumes. Control: Wear mask.

- Specific (Pass): Hazard: Accumulation of welding gases (Argon) leading to asphyxiation. Control: Continuous gas monitoring at breathing zone; forced air ventilation at 2000 CFM; impossible to lock trigger on welding torch.

Pro Tip: Ask the contractor: “Who writes these?” If they say “The Safety Manager in the Head Office,” that’s a fail. RAMS should be written by the Supervisors and Workers who actually do the job.

4. Regulatory Violation History: The Ethical Compass

Government regulators (OSHA, HSE UK, EPA) do not catch everyone. If a contractor has been caught and fined, it is usually the tip of the iceberg.

“Serious” vs. “Willful”

- Serious Violation: This means a hazard existed that could cause death or serious harm, and the employer knew or should have known about it. One or two of these might be isolated incidents.

- Willful / Repeat Violation: This is the deal-breaker. A “Willful” violation means the contractor knew it was illegal and dangerous (e.g., sending men into a trench without shoring) but did it anyway to save money or time. This indicates a malignant corporate culture.

The “Phoenix” Company

Be aware of contractors who dissolve a company after a major fatality or massive fine, then reopen the next day under a new name but with the same owners and equipment.

- Check: Look at the ownership history. If the company is “New,” ask about the owner’s previous ventures.

5. HSE Management System Accreditation: The Skeleton vs. The Muscle

ISO 45001 (Safety) and ISO 14001 (Environment) are valuable standards, but they are just frameworks—skeletons.

The Audit Trap

External auditors (certification bodies) usually visit for a few days once a year. They check documents, interview a few pre-selected people, and leave.

The “Shelfware” Problem: Many companies pay consultants to write beautiful manuals that sit on a shelf (or a server) and are never opened by the site team.

System vs. Culture:

- The System (ISO Certificate): Says “We have a procedure for working at heights.”

- The Culture (Reality): Is whether the guy on the night shift actually hooks his harness to an anchor point when no one is watching.

How to Verify

Don’t be impressed by the certificate on the wall. Ask to see an Internal Audit Report.

- A good company audits itself harder than the regulator does. If their internal audits show “Non-Conformances” (failures) and “Corrective Actions” (fixes), that is excellent. It means the system is alive and working.

- If their internal audits are all perfect with no findings, their system is fake.

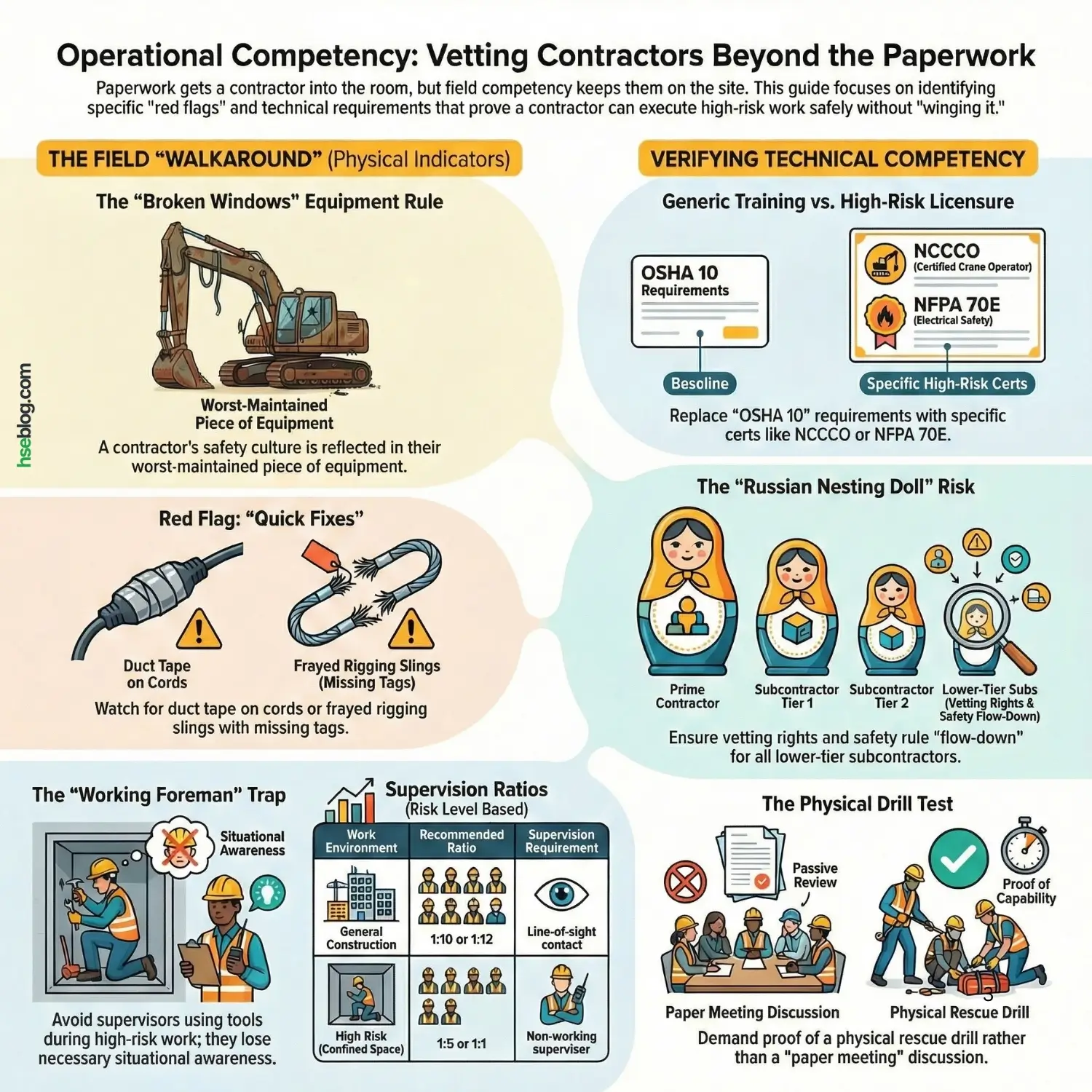

Operational & Field Competency

Can they actually do the specific work safely?

Paperwork gets a contractor into the room; operational competency keeps them on the site. This section is where the rubber meets the road. In my experience, most catastrophic failures happen not because the company didn’t have a policy, but because they didn’t have the capability to execute the work in the field.

6. Scope-Specific Competency: The “Jack of All Trades” Danger

Many contractors are desperate for revenue. They will tell you, “Yes, we do civil, mechanical, electrical, and scaffolding.” But in reality, they are only good at one, and they “wing it” on the others.

The “Generic Training” Fallacy

I often see training matrices filled with generic certifications: “General Safety Induction,” “Fire Awareness,” or “OSHA 10.” These are great for awareness, but they do not prove competency.

The Gap: A worker can sit through a 10-hour OSHA class and still have no idea how to rig a complex load or isolate a high-voltage breaker.

The Check: You need High-Risk Licensure.

- Lifting: Don’t ask for “Rigger Training.” Ask for “NCCCO Rigger Level 1 or 2” (or local equivalent).

- Electrical: Ask for “NFPA 70E Arc Flash Qualified” certification, not just “Electrical Safety.”

- Welding: Ask for the specific welder qualification records (WQRs) for the position and material they will be welding (e.g., 6G position on carbon steel).

The “Similar Project” Proof

Ask for a reference from a project they completed in the last 12 months that involved the exact high-risk scope you are hiring them for. If they are pouring concrete for a bridge, I don’t care if they successfully poured a sidewalk. The physics, the risks, and the competencies are totally different.

7. Equipment Asset Integrity: The Visible Culture

You can tell everything about a contractor’s safety culture by looking at their worst piece of equipment.

The Psychological Link

There is a direct psychological link between maintenance and safety.

- The Logic: If a contractor is willing to ignore a leaking hydraulic hose to save $100 and keep working, they are definitely willing to ignore a missing handrail or an uninspected harness to save 10 minutes.

- The “Broken Windows” Theory: If the equipment is dirty, rusted, and bypassed, the workers feel that “nobody cares.” This leads to sloppy behavior, discarded PPE, and eventually, accidents.

What to Inspect (The Walkaround)

When you visit their yard or current site, look for these specific indicators:

- The “Quick Fixes”: Look for duct tape on electrical cords, wire holding guards in place, or cardboard under leaking engines. These are signs of a “production over safety” mindset.

- Lifting Gear: Go to their rigging box. If you find synthetic slings that are sun-bleached, frayed, or have missing tags, disqualify them. Rigging is the single most critical failure point in heavy industry.

- Maintenance Logs: Ask to see the log for a specific crane or excavator. If the last entry was six months ago, or if all the checkboxes are ticked in the exact same ink, they are faking the maintenance.

8. Supervision-to-Worker Ratio: The Span of Control

The number one reason for unsafe acts is lack of supervision. Workers will naturally take the path of least resistance (shortcuts) unless a leader is there to set the standard.

The “Working Foreman” Trap

Contractors love to bid low by proposing a “Working Foreman.” This is a supervisor who also uses tools and works alongside the crew.

- Why it Fails: You cannot supervise a critical lift or a confined space entry if your hood is down and you are welding. You lose situational awareness.

- The Requirement: For high-risk work, demand a Non-Working Supervisor. Their only tools should be a radio and a gas monitor. Their job is to watch, direct, and protect.

The Magic Numbers

- General Construction: 1:10 or 1:12 is acceptable.

- High Risk (Confined Space / HazMat): 1:5 or even 1:1.

- Geographic Spread: Even if the ratio is 1:10, if those 10 workers are spread across three different floors or two miles of pipeline, the supervision is effectively zero. The ratio must be based on line of sight.

9. The “Subcontractor Management” Clause: The Hidden Risk

I call this the “Russian Nesting Doll” of risk. You hire a Tier 1 Global Contractor (Safe). They hire a mechanical sub (Okay). That sub hires a local labor broker (Dangerous) to do the actual grinding and cutting.

The Risk Transfer

When a contractor subcontracts work, they are often trying to offload the risk and the cost.

- The Danger: The people actually doing the work on your site might not have been vetted by you, might not have your training, and might be paid piece-rate (which encourages rushing).

The “Right to Reject”

In your contract, you must include a clause that gives you:

- Vetting Rights: You must see the safety stats of their proposed subcontractors before they are allowed on site.

- The Blacklist: If they bring a sub on site who violates your rules, you have the right to remove that sub immediately, and the main contractor is liable for the delay.

- Flow-Down Requirements: The main contractor must prove that your safety rules (PPE standards, reporting requirements) are legally written into their contracts with the subs.

10. Emergency Response Capabilities: The “Golden Hour”

Hope is not a strategy. I have seen contractors freeze when an accident happens because they assumed “someone else” would handle it.

Why “Call 911” is a Failure

In complex industrial sites, “Calling 911” is insufficient for immediate life threats.

- Confined Space: Firefighters may take 15 minutes to arrive and another 30 minutes to set up. A worker in an oxygen-deficient atmosphere has 4 minutes before brain damage starts. The contractor must have a retrieval team ready at the hole.

- Work at Height: If a worker falls and is hanging in their harness, they can develop Suspension Trauma (orthostatic intolerance) in as little as 10-15 minutes, which can be fatal. The fire department won’t get there in time. The contractor needs a rescue kit (e.g., Gotcha Kit) and trained climbers to get them down now.

The Drill Test

Ask the contractor: “Show me the record of your last rescue drill.”

- Paper Drill: “We talked about it in the meeting.” (Fail).

- Physical Drill: “We suspended a dummy from the tower and the crew practiced lowering it using the rescue descent device.” (Pass).

- Equipment: Do they own the rescue gear? Or do they plan to “rent it if needed”? If they don’t own it, they don’t know how to use it.

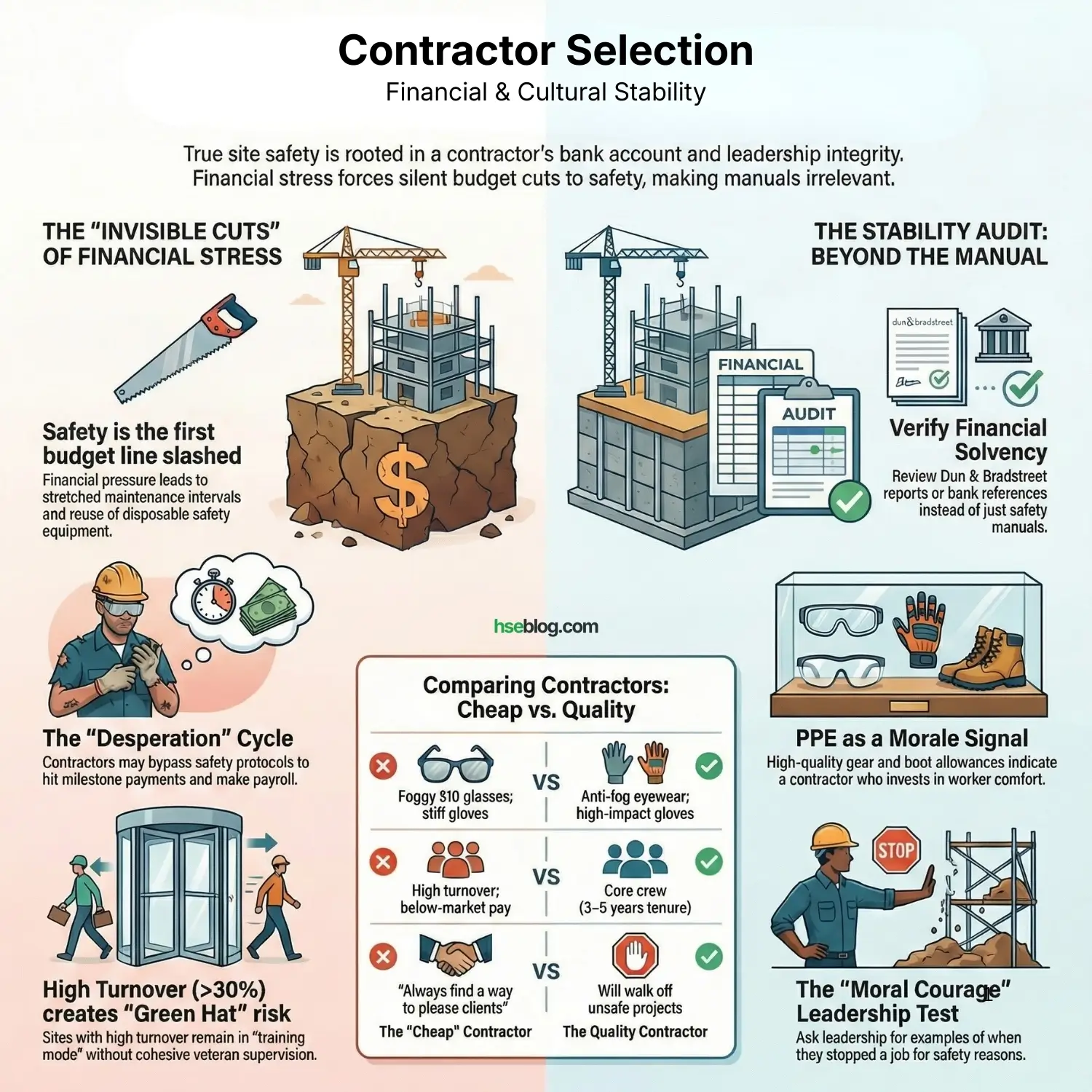

Financial & Cultural Stability

Safety costs money. If they are broke, safety is the first thing cut.

In my years investigating incidents, I have found that the root cause often isn’t on the site—it’s in the bank account. Safety is an overhead cost. It requires buying things that don’t directly generate profit (training, guards, inspections). When a contractor is financially stressed, safety is the first budget line to be slashed, usually in subtle ways you won’t see until something snaps.

11. Financial Solvency: The “Desperation” Cycle

I once audited a rigging company that was weeks away from bankruptcy. I found they were using synthetic slings that were three years past their retirement date. Why? Because a new set cost $5,000, and they didn’t have it.

The Invisible Cuts

A contractor under financial pressure will not send you an email saying, “We are cutting safety.” Instead, they will:

- Stretch Maintenance Intervals: Changing oil every 1,000 hours instead of 500.

- Ghost the Suppliers: If they owe the PPE supplier money, the supplier stops shipping gloves. Workers start reusing disposable items.

- Push the Crew: They need to hit a milestone payment this Friday to make payroll. This creates immense pressure to bypass safety protocols (like permit approvals) to get the work done faster.

The Check

Do not just look at their safety manual. Look at their Dun & Bradstreet report or ask for a bank reference. If they are fighting to survive, they will drag you down with them.

12. Turnover and Retention Rates: The “Green Hat” Risk

There is a direct correlation between “Short Service Employees” (SSEs) and injury rates.

The “Tribal Knowledge” Factor

On a safe site, the veterans police the rookies. An experienced foreman knows that “when the wind hits the north face, the crane swings.” A new hire doesn’t know that.

- High Turnover (>30%): If 1 in 3 workers is new every year, your site is permanently in “training mode.” There is no cohesion. The workers are strangers to each other, which means they won’t intervene if they see a peer doing something unsafe.

- The Revolving Door: If a contractor pays below market rate, they will lose their best people to the competition. You are left with the workers who couldn’t get hired elsewhere.

The Fix

Ask for their average employee tenure. You want a core crew that has been together for 3–5 years. They have a “brother’s keeper” mentality that no rulebook can replicate.

13. Medical Surveillance & Fitness for Duty: The “Internal” Hazard

We spend a lot of time looking at external hazards (holes, wires, gas), but often the hazard is the worker’s own physical condition.

Beyond the Drug Test

Yes, you need a 12-panel drug screen to catch impairment. But real Occupational Health is deeper:

- Respiratory Fit Testing: If they are working with silica or welding fumes, do they have a current quantitative fit test record? If not, that expensive respirator is just a face decoration.

- Audiometric Testing: Are they tracking hearing loss?

- Fit for Duty: I have seen operators have heart attacks in crane cabs because their employer never checked their blood pressure or cardiac health.

- The Liability: If a worker develops occupational asthma on your site because the contractor didn’t monitor their health, you could be named in the lawsuit.

14. PPE Standards and Provision: The Morale Signal

You can tell how much a company respects its workers by looking at their boots and gloves.

The “Bare Minimum” vs. “High Performance”

The Cheap Contractor: Issues the cheapest, stiffest leather gloves and $10 safety glasses that fog up immediately.

- Result: Workers take the glasses off to see better, and get debris in their eyes. They take the gloves off to handle small screws, and get cut.

The Quality Contractor: Issues high-impact mechanics gloves (protection + dexterity) and anti-fog, comfortable eyewear.

- Result: Workers wear the gear because it works.

Pro Tip: Look at the boots. If the contractor provides a boot allowance or high-quality footwear, it reduces fatigue. A tired worker makes bad decisions. Investing in comfort is investing in safety.

15. Environmental Track Record: The Discipline Indicator

Safety and Environment are cousins. They both require strict adherence to procedure and discipline.

The “Broken Windows” of the Environment

If a contractor is willing to dump used oil in a hole behind the workshop, they are demonstrating a total lack of integrity.

- Spill Response: Do they have spill kits on their machines? Are the kits actually full, or are they filled with trash?

- Dust & Noise: A contractor who ignores dust control (affecting neighbors) lacks situational awareness.

- The Regulator Risk: Environmental fines are often massive and public. If your contractor gets fined for illegal dumping while working on your project, your company’s logo is the one on the news.

16. Senior Leadership Engagement: The “Moral Courage” Test

This is the final and most important filter. Culture flows down. If the owner is a cowboy, the site manager will be a cowboy.

The Interview Strategy

When you interview the contractor’s leadership team, ignore the Sales Director. Look at the Operations Director or the Owner.

Ask this specific question:“Tell me about a time you stopped a job or fired a client because they asked you to do something unsafe.”

- Bad Answer: Silence, or “We always find a way to make the client happy.” (This means they will break rules to please you).

- Good Answer: “Last year, we walked off the XYZ project because the client refused to fix the scaffolding. We lost $50k, but we kept our guys safe.”

You want a contractor who fears hurting a worker more than they fear losing a contract. That is the only partner worth having.

Conclusion

I have never regretted firing a contractor during the selection phase, but I have deeply regretted hiring the wrong one. The selection process is your only leverage point. Once they are mobilized on site, removing them is a legal and logistical nightmare that costs millions.

Use these 16 factors to peel back the layers of marketing. You are not looking for a contractor who says they are safe; you are looking for a contractor who treats safety as an operational discipline, financed properly, and led by competent supervisors. Choose the partner who is willing to tell you “No” when the risk is too high—they are the ones who will save your reputation and your project.