I once walked into a busy logistics terminal just in time to see a 3-ton counterbalance forklift whip around a blind corner with its forks raised at chest height. A picker was stepping out from the racking at that exact second. I didn’t have time to shout; I just watched the operator slam the brakes, sending the unsecured pallet sliding off the tines and crashing inches from the pedestrian’s steel-toed boots. The silence that followed that crash was heavier than the load itself. That wasn’t an “accident”—it was a failure of basics: speed, visibility, and load stability.

Forklifts are the workhorses of our industry, but they are also statistically one of the most dangerous pieces of equipment on any site. Today’s talk isn’t just about how to drive; it’s about the physics that will kill you if you ignore them. Whether you are behind the wheel or walking the floor, you need to respect the machine’s limits and the massive blind spots that come with it. We are going to cover the non-negotiables that keep the rubber side down and everyone else safe.

TL;DR: Key Takeaways

- Eye Contact is Mandatory: Never assume a pedestrian sees you; force eye contact before moving.

- Seatbelts Save Lives: In a tip-over, the seatbelt keeps you inside the cage—jumping out is fatal.

- Stability Triangle: Keep loads low and centered; high speeds and tight turns flip trucks.

- Blind Spots: Sound the horn at every intersection and cross-aisle, no exceptions.

- Park Safe: Forks flat on the ground, parking brake set, and keys removed every time you exit.

Pre-Operational Checks: The “Circle of Safety”

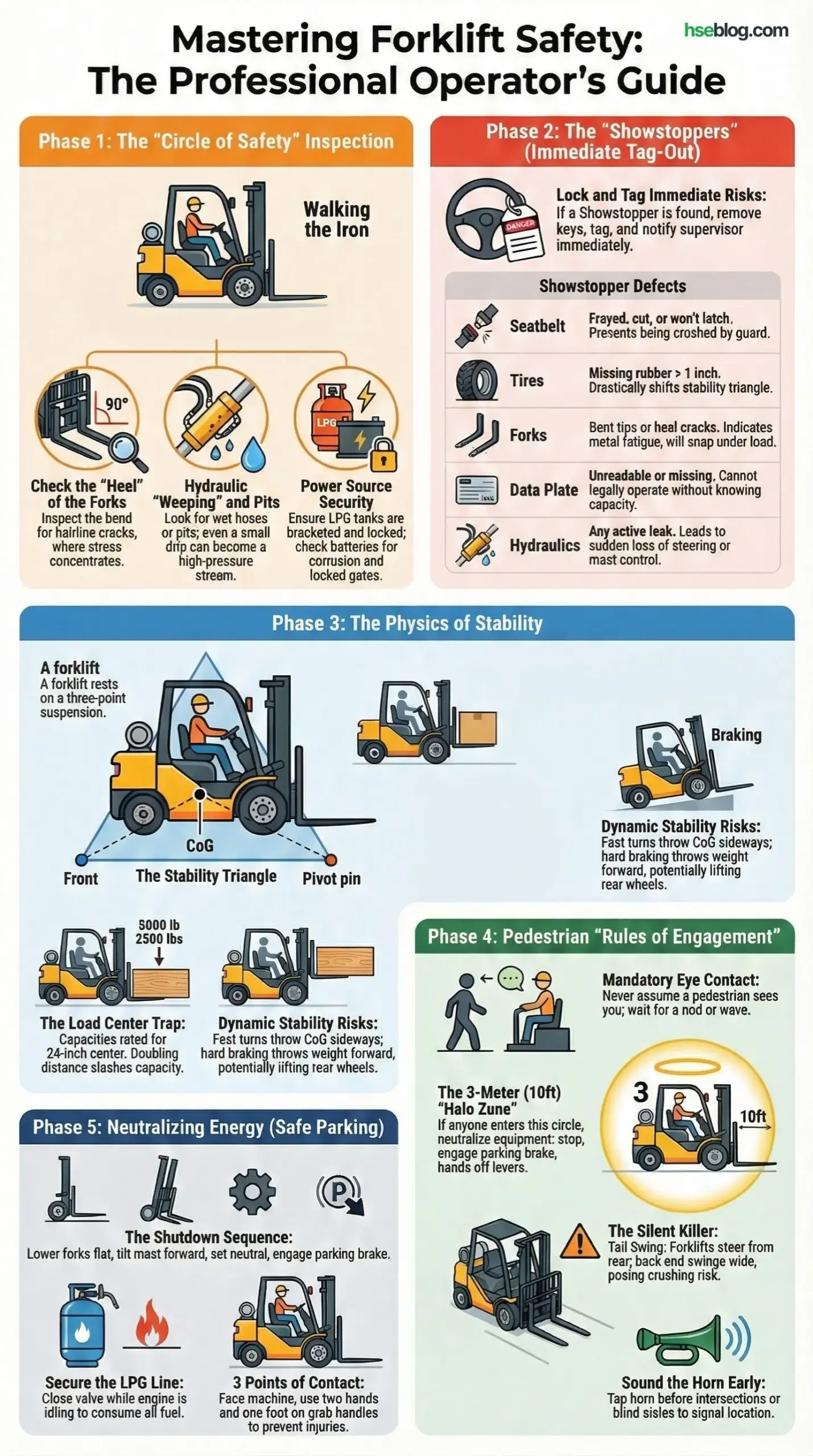

The “Circle of Safety” is your primary defense against mechanical failure. It is a visual, physical inspection of the forklift’s exterior before you enter the cab. In the field, we call this “walking the iron.” It is not a paperwork exercise; it is a survival habit. If you are just ticking boxes without looking, you are eventually going to hurt someone.

1. The Anatomy of the Circle

The concept is simple: start at the front left corner of the truck and walk a full circle around it. You are looking for anything that looks broken, loose, leaking, or missing.

The Tires and Wheels

Tires are the only thing connecting your machine to the ground. On a forklift, they act as the suspension.

- Chunking: Look for large pieces of rubber falling off the tire. This makes the truck unstable, especially with a high load.

- Debris: Check for banding straps, wire, or shrink wrap wrapped around the axle. I’ve seen wire wrap so tight it cut through the axle seal, causing a massive leak.

- Lug Nuts: Look for rust streaks coming from the lug nuts—this usually means they are loose.

The Hydraulic System

The hydraulic system is the muscle of the machine.

- The Floor Check: Before you look at the truck, look at the floor under the truck. Any fluid spot (red, clear, or black) is an immediate stop.

- Hoses and Cylinders: Look at the mast chains and hoses. Are the hoses “weeping” (wet with oil)? Is the outer rubber jacket chafed, revealing the metal braiding underneath?

- Lift Cylinders: Check the chrome rods for pits or scores. Rough spots on the chrome will tear the seals apart.

The Forks and Mast

This is the business end of the forklift. If this fails, the load falls.

- Heel Cracks: Inspect the “heel” of the fork (the 90-degree bend). This is where all the stress concentrates. Even a hairline crack here warrants immediate removal from service.

- Locking Pins: Kick the forks. If they slide freely, the locking pins are not engaged or are broken. A sliding fork can cause a load to shift and tip the truck over.

- Mast Rails: Ensure there is no debris or metal shards in the mast channels.

Power Source

- Propane (LPG): Check that the tank is bracketed securely and the locating pin is locked. Listen for a hissing sound at the connection. Smell for rotten eggs.

- Battery (Electric): Look for “cauliflower” corrosion on the cables. Check the water levels. Ensure the battery gate is locked shut so the battery doesn’t slide out during a turn.

2. The “Showstoppers” (Immediate Tag-Out)

In my experience, operators often find a small issue and think, “I’ll report it later.” This is dangerous. As a safety authority, I teach operators that the following items are Showstoppers. If you find one during your Circle of Safety, you take the keys, attach a “Danger: Do Not Operate” tag, and notify a supervisor immediately.

| Component | Defect | Why it’s a Showstopper |

| Seatbelt | Frayed, cut, or won’t latch | In a tip-over, you will fall out and be crushed by the overhead guard. |

| Tires | Missing rubber > 1 inch | Drastically changes the stability triangle; causes tip-overs. |

| Forks | Bent tips or heel cracks | The metal is fatigued and will snap under load. |

| Data Plate | Unreadable or missing | You cannot legally operate a crane or forklift without knowing its capacity. |

| Hydraulics | Any active leak | A drip becomes a stream under pressure, leading to loss of control. |

Pro Tip: Carry a rag in your back pocket during the inspection. If you see a spot on a hose and you aren’t sure if it’s a leak or just grime, wipe it clean. If it comes back wet instantly, it’s a leak.

Understanding Stability and Capacity

Most operators treat a forklift like a car. They think if the four wheels are on the ground, they are safe. This is a fatal misconception. A forklift is a suspension-less seesaw balanced on three points (even on a four-wheel truck). Understanding Stability and Capacity isn’t about memorizing math; it’s about understanding that every time you touch a lever or turn the wheel, you are actively fighting gravity. If you lose that fight, the machine tips over, and the seatbelt is the only thing keeping you inside the cage.

1. The Stability Triangle

To an engineer, a forklift is a lever. The front wheels are the fulcrum (pivot point). The load on the forks is the weight you are trying to lift. The engine and heavy counterweight at the back are what keep you on the ground.

The Three-Point Suspension

Even if your forklift has four wheels, it rests on a three-point suspension system:

- Front Left Wheel

- Front Right Wheel

- The Pivot Pin of the Rear Steer Axle (Center of the rear axle)

Connect these three points, and you get the Stability Triangle.

The Center of Gravity (CoG)

There is an invisible dot called the “Combined Center of Gravity” (CCG). This is a mix of the truck’s weight and the load’s weight.

- Empty Truck: The CoG is near the rear (because of the heavy counterweight).

- Loaded Truck: The CoG moves forward toward the front wheels.

- Raised Load: The CoG moves up and forms a “pyramid” shape.

The Golden Rule: As long as that invisible CoG dot stays inside the triangle, you are safe. If it crosses the line—due to turning, braking, or lifting too heavy—the truck tips.

2. Capacity: Reading the Data Plate

I cannot stress this enough: The big number painted on the side of the truck (e.g., “30” for 3,000 lbs) is essentially marketing. The Data Plate is the only truth.

The Load Center Trap

Standard capacity is usually rated at a 24-inch load center. This means the center of your load must be 24 inches from the face of the forks (basically a standard 48-inch pallet).

- The Danger: If you pick up a long load (like 8-foot pipe or lumber), the center of that load is now 48 inches out.

- The Consequence: This acts like a longer wrench turning a bolt. It creates more leverage. A 5,000 lb truck might only be able to lift 2,500 lbs if the load center is pushed out.

Attachments Reduce Capacity

I’ve stopped jobs where operators slapped a drum-grabber or fork extensions on a truck without checking the new rating.

- Added Weight: The attachment itself is heavy, eating up your lifting capacity.

- Extended Load Center: Attachments push the load further away from the fulcrum.

- The Rule: If you add an attachment, you must have a new Data Plate installed that lists the capacity with that specific attachment.

3. Dynamic Stability: Physics in Motion

Static stability (sitting still) is easy. Dynamic stability (moving) is where accidents happen. Forces change instantly when you move.

| Action | Physics Reaction | The Risk |

| Braking Hard | Momentum throws the load weight forward. | The rear steer wheels lift off the ground; you lose steering and can tip forward. |

| Turning Fast | Centrifugal force throws the CoG sideways. | The CoG exits the side of the stability triangle; the truck tips over sideways. |

| Lifting High | The CoG moves up, creating a “bobblehead” effect. | Tiny movements at the ground become massive sways at the top. |

| Tilt Forward | Moves the CoG forward dramatically. | Never tilt forward with a raised load unless you are over a rack; you will tip forward. |

Pro Tip: The “pyramid” effect is real. When your forks are down, your stability base is solid. When your forks are up 15 feet, your stability is as fragile as an inverted pendulum. Never, ever travel with the load raised more than 4–6 inches.

Pedestrian Awareness and Communication

The interaction between forklifts and pedestrians is the single greatest risk in any warehouse or plant. A 9,000 lb machine with hard cushion tires doesn’t just bruise; it crushes bone. As an operator, you are driving a weapon in a crowded room. You cannot rely on pedestrians to be smart. You have to drive as if everyone around you is trying to get hit.

1. The Mechanics of Blind Spots

Most pedestrians have no idea what you can’t see. They think because you are sitting high up, you see everything. You know the reality is different.

The “Mast Blindness”

The mast assembly, hydraulic hoses, and the load itself create a massive blind spot directly in front of you.

- The Risk: A pedestrian walking closely in front of the forklift can completely disappear behind the load.

- The Fix: If you can’t see the floor in front of you, you drive in reverse. Period.

The “Tail Swing” (The Silent Killer)

Forklifts steer with the rear wheels. This means the back end swings wide when you turn—opposite to the turn direction.

- The Risk: Pedestrians standing “safely” to the side of the truck often get pinned against a wall or rack when the operator initiates a turn.

- The Fix: Check your swing radius before turning. If a pedestrian is standing near a fixed object (wall/rack), do not move until they clear the area.

2. The Non-Negotiable Rules of Engagement

In my sites, we establish “Rules of Engagement” that are black and white. There is no grey area when flesh meets steel.

The Eye Contact Rule

This is the most critical tool you have.

- The Procedure: If a pedestrian approaches your path or is working nearby, stop the machine. Wave at them. Wait for them to look at you and acknowledge you (a nod or a wave back).

- The Reality: If they are looking at their phone, looking at a clipboard, or talking to someone else, they do not see you, even if they are looking in your direction. Assume they are about to step in front of you.

The 3-Meter (10ft) Halo

We call this the “Halo Zone.”

- The Rule: Imagine a 3-meter circle around your truck. If a pedestrian steps into that circle, you neutralize the equipment. That means: Stop. Parking brake on. Hands off levers.

- Why: If you sneeze, slip on a pedal, or a hydraulic hose bursts, you can lurch forward 3 feet instantly. You need that buffer zone.

3. Communication Tools

You cannot scream over the sound of a diesel engine or a busy factory floor. You must use your machine to speak for you.

The Horn: It is not an insult; it is a location signal.

- Short Tap: “I am here.” (Use at intersections).

- Long Blast: “DANGER / MOVE.”

- The Policy: Sound the horn before you stick the forks out of a blind aisle, not after.

Lights (Blue Spots & Red Zones):

- Many modern trucks project a blue light on the floor behind them or a red “danger zone” line on the sides.

- Operator Duty: Ensure these are clean and working. They are the only warning a pedestrian looking down at a phone might see.

Hand Signals: Agree on simple signals with your floor team. A “Stop” hand is universal. A “Thumbs Up” means clear to proceed. Never rely on a vague nod.

I tell my teams: “Pedestrians always have the Right of Way, even when they are dead wrong.” It doesn’t matter if they walked outside the yellow lines. It doesn’t matter if they were texting. If you hit them, you are responsible. You are the professional operator. You control the hazard. Slow down, force eye contact, and never assume that the person walking by hears your backup alarm.

Leaving the Cab: Safe Parking Procedures

Parking a forklift isn’t just about stopping the wheels; it is about completely neutralizing the machine’s energy. A forklift left improperly secured is a stored-energy bomb waiting for a trigger—whether it’s gravity, a hydraulic failure, or an untrained curious worker. The job isn’t done until the machine is “cold” and incapable of movement.

1. The Shutdown Sequence (Neutralizing Energy)

You cannot just turn the key off and walk away. You must systematically bleed the energy out of the machine before you leave the seat.

The “Grounding” Rule The most common hazard I see on walkthroughs is “shin-busters”—forks left hovering 4 to 6 inches off the ground.

- Forks Flat: Lower the forks until they rest completely on the floor. If possible, tilt the mast forward slightly so the fork tips touch the ground. This prevents tripping and removes hydraulic pressure from the lift cylinders.

- Neutralize Controls: Move the directional lever (Forward/Reverse) to Neutral. Jiggle the hydraulic levers to relieve any residual pressure.

- The Parking Brake: This is non-negotiable. The transmission will not hold a forklift. You must set the handbrake or engage the electronic parking brake before you release the foot brake.

Pro Tip: If you are driving an LPG (Propane) truck, close the valve on the tank while the engine is still idling. Let the engine die by consuming the fuel in the line. This ensures no pressurized gas is left in the hose near the hot engine block.

2. Location and Security

Where you park is just as important as how you park. I have failed audits because operators parked perfectly—but in front of a fire extinguisher.

The “No-Park” Zones Before you cut the engine, look around.

- Emergency Routes: Never block fire exits, aisles, or stairwells.

- Critical Equipment: Keep clear of electrical panels, eyewash stations, and firefighting equipment.

- Blind Spots: Do not park on corners or right behind doorways. Someone coming through that door won’t expect a steel wall.

Control Access

- Take the Key: If you leave the key in, you are inviting the night shift cleaner or a delivery driver to “just move it real quick.” That is how untrained accidents happen.

- Chock the Wheels: If you are forced to park on an incline (which you should avoid), you must physically block the wheels with chocks. The parking brake alone is not rated for steep grades.

3. Exiting the Machine (The Dismount)

It sounds simple, but getting out of the cab is a high-injury activity. We see more twisted ankles and blown knees from dismounting than from collisions.

Face the Machine

- No Jumping: The distance from the cab floor to the concrete is higher than you think. Jumping shocks your spine and knees.

- 3 Points of Contact: Maintain two hands and one foot (or two feet and one hand) on the grab handles and steps until you are on the ground.

- Check the Ground: Look down before you step down. Oil spots, loose debris, or uneven concrete are waiting to slip you up.

Discipline is what separates a professional operator from a steering wheel holder. It takes an extra ten seconds to lower the forks, set the brake, close the valve, and pocket the key. Those ten seconds prevent runaways, fires, and unauthorized use. When you walk away from your machine, leave it in a state where it cannot hurt anyone, no matter what happens next.

Conclusion

Forklift safety isn’t about skill—it’s about discipline. The best operators I’ve worked with aren’t the ones who can stack pallets the fastest; they are the ones who refuse to move a load until the path is clear and the machine is checked. Remember, when you are behind the wheel, you are driving a weapon. Respect the weight, respect the physics, and respect the people walking around you. Do not become the reason someone doesn’t go home to their family tonight.