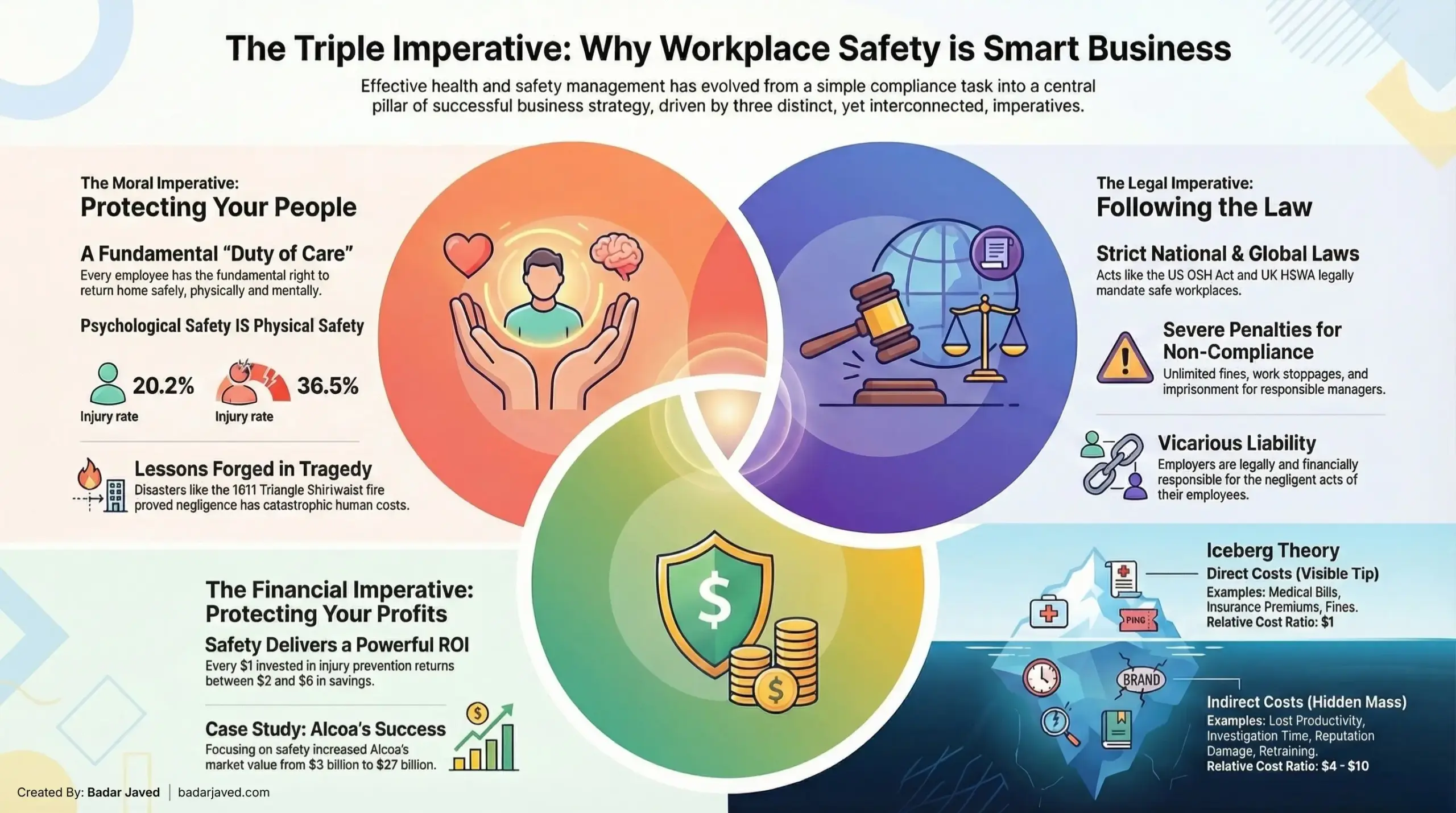

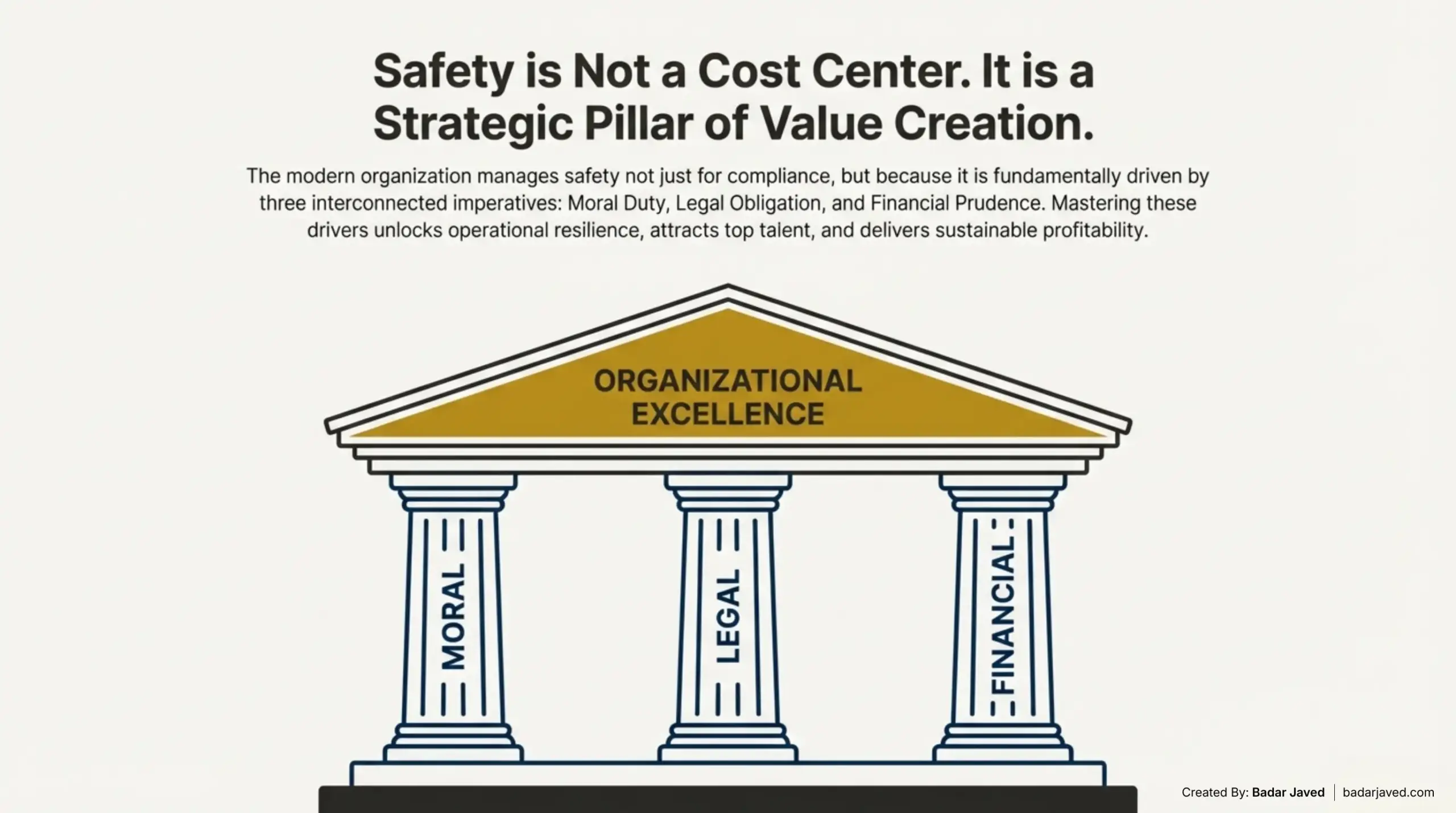

The modern industrial landscape is defined by a complex interplay of ethical obligations, regulatory frameworks, and economic pressures. Within this dynamic environment, the management of Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) has evolved from a peripheral compliance activity into a central pillar of organizational strategy. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the fundamental question: “Why do we manage health and safety?” By dissecting the tripartite drivers of Moral, Legal, and Financial imperatives, this article demonstrates that effective safety management is not merely a statutory requirement but a critical determinant of operational resilience, human capital retention, and long-term profitability.

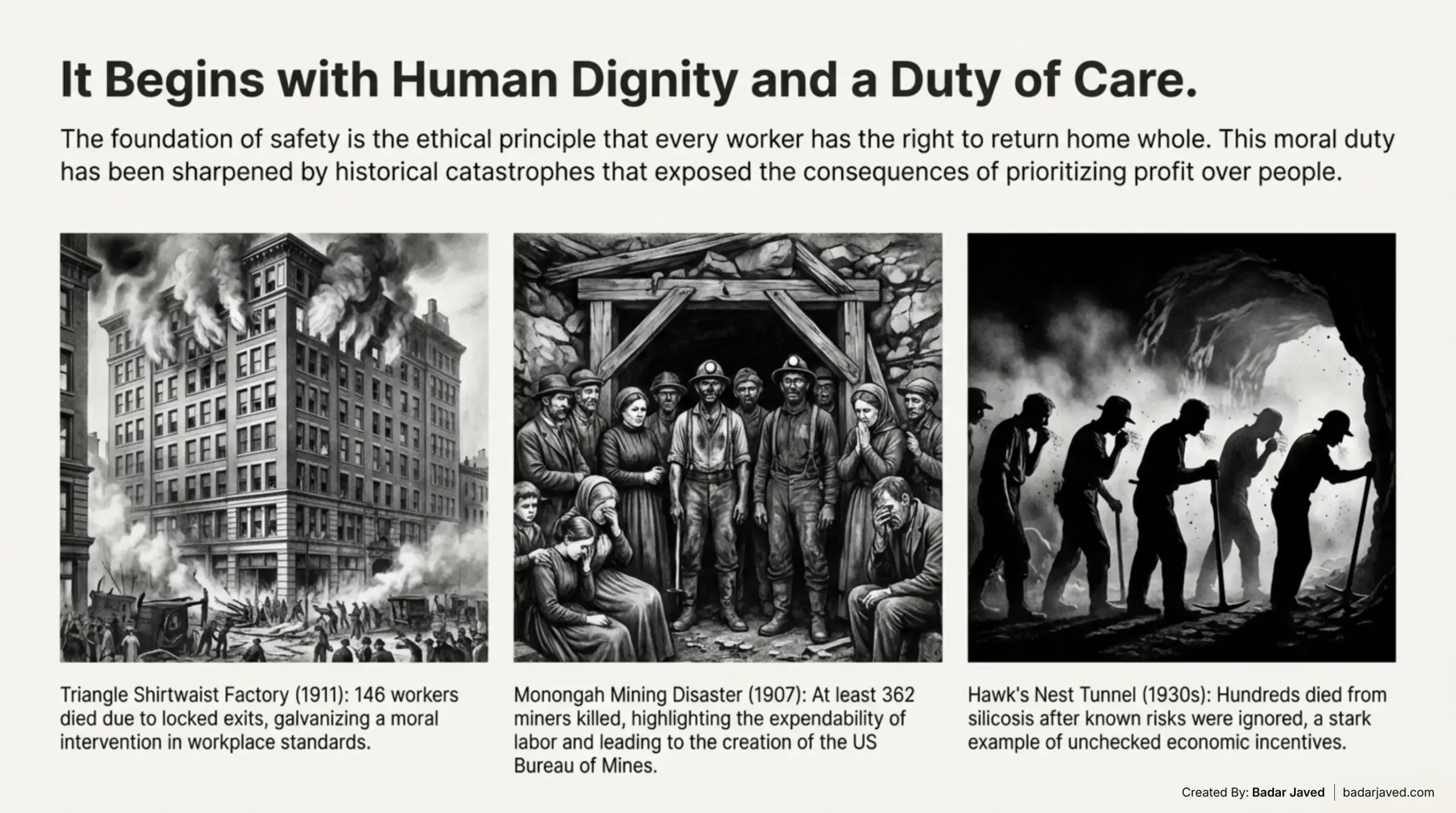

Historically, the approach to worker safety was reactive, often necessitated by catastrophic failures that shocked the public conscience. From the ashes of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire to the devastating legacy of the Monongah Mining Disaster, the moral argument for safety has been forged in tragedy. Today, that moral duty extends beyond preventing physical injury to encompass psychological well-being, recognizing that a “safe” workplace is one where employees are free from both bodily harm and mental distress. The “Duty of Care” is now understood as a universal ethical mandate, asserting that no commercial objective justifies the loss of human life or dignity.

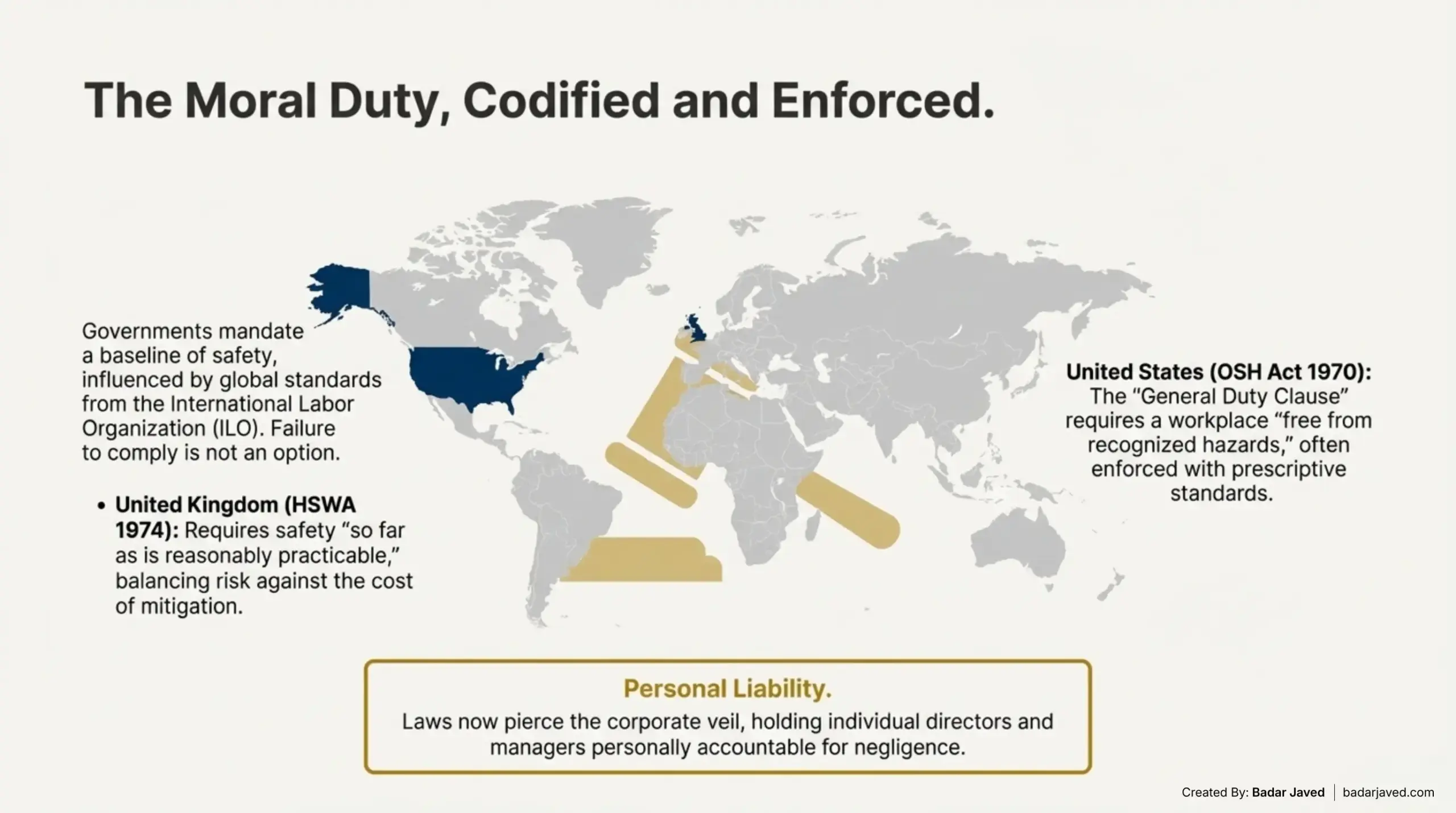

Legally, the landscape has shifted from simple oversight to rigorous enforcement. Governments worldwide, influenced by International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions, have established comprehensive statutes such as the UK’s Health and Safety at Work Act (1974) and the US Occupational Safety and Health Act (1970). These laws impose strict liability on organizations and their directors, piercing the corporate veil to hold leadership personally accountable for negligence. The legal imperative serves as a baseline, ensuring that the moral duty is codified and that failure to protect workers results in severe punitive consequences, including imprisonment and unlimited fines.

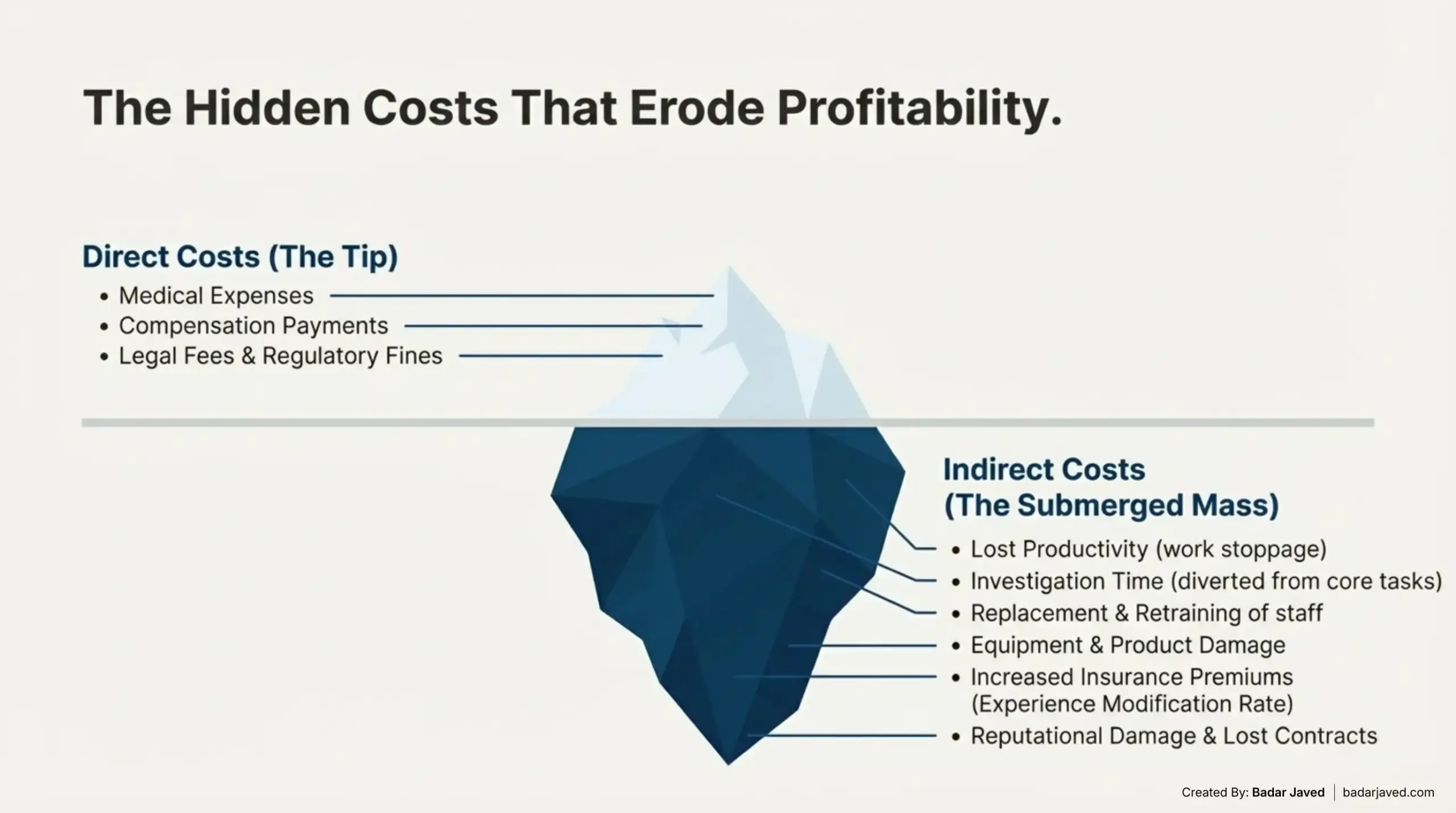

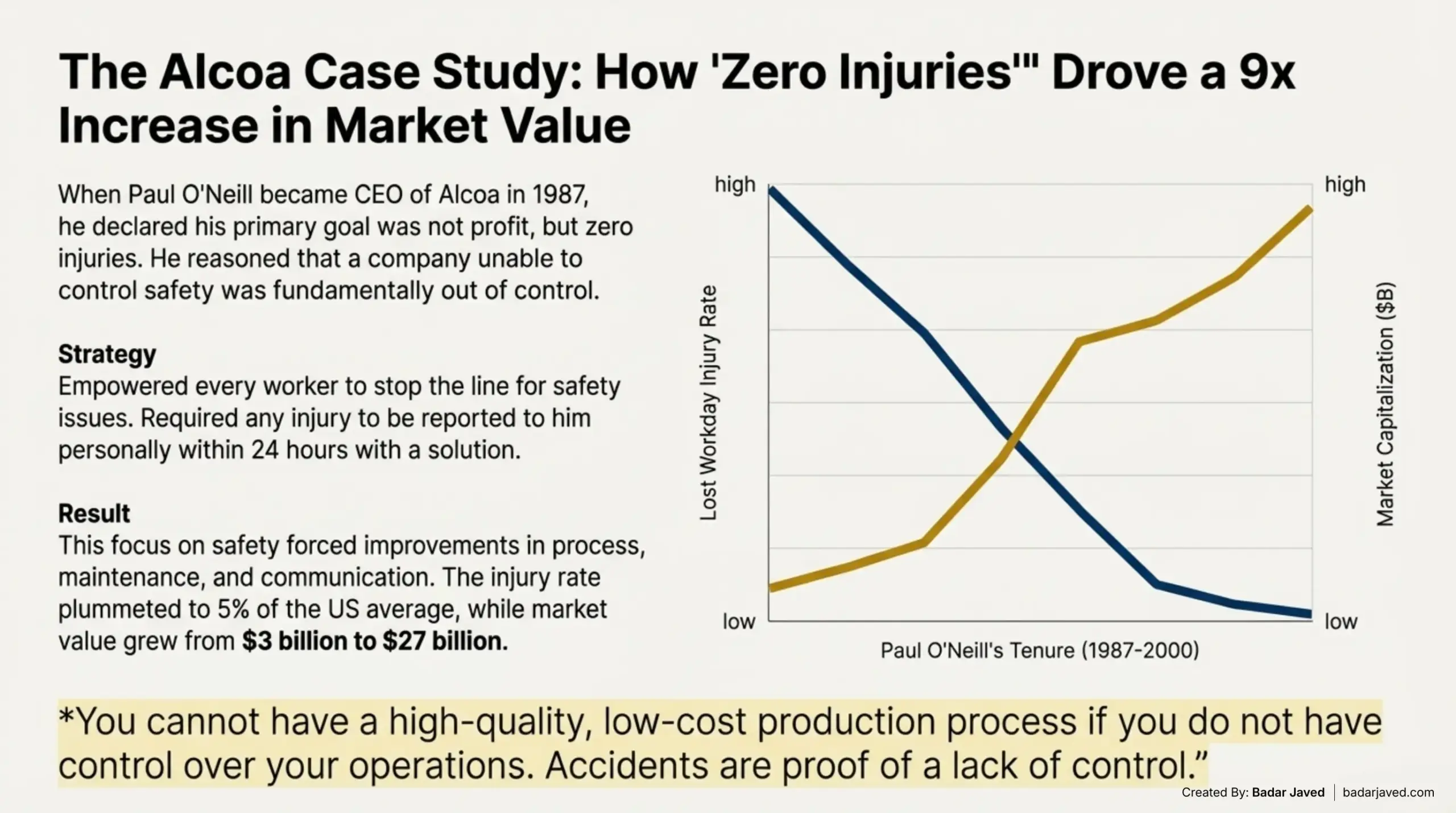

Financially, the “Iceberg Theory” of accident costs reveals that the visible expenses of medical treatment and insurance premiums represent only a fraction of the total economic impact. The hidden, indirect costs—ranging from lost productivity and investigation time to reputational damage and retraining expenses—can be four to ten times greater than direct costs. Conversely, proactive investment in safety yields a substantial Return on Investment (ROI), with studies indicating that every dollar spent on injury prevention returns between $2 and $6 in savings. The transformative case study of Alcoa under Paul O’Neill illustrates this vividly: by prioritizing safety as a proxy for operational excellence, the company increased its market value from $3 billion to $27 billion, proving that the safest companies are often the most profitable.7

This blog also explores the emerging frontiers of OHS, including the critical link between psychological safety and physical injury rates, the role of ISO 45001 in standardizing global best practices, and the integration of AI and predictive analytics in shaping the future of risk management. Ultimately, the analysis concludes that managing health and safety is the primary indicator of a high-performance culture, essential for attracting top talent, securing investor confidence, and ensuring sustainable business continuity in an increasingly risk-averse world.

The Strategic Context of Safety

In the contemporary business lexicon, “Health and Safety” is often abbreviated to a department title or a compliance checklist. However, the true scope of Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) management transcends these administrative boundaries. It is a multidisciplinary endeavor that touches upon engineering, psychology, law, economics, and ethics. The decision to manage health and safety is rarely driven by a single factor; rather, it is the result of a convergence of pressures that shape the modern corporate entity.

The Shift from Reactive to Proactive

Traditionally, safety management was reactive. Organizations managed safety by counting accidents after they occurred—a metric known as “lagging indicators.” If the accident rate was low, the workplace was deemed safe. This methodology was fundamentally flawed, as it relied on the presence of failure to measure success. Today, the paradigm has shifted toward proactive management. Leading organizations utilize “leading indicators”—such as near-miss reporting, safety audits, and employee engagement surveys—to identify hazards before they manifest as injuries. This shift is driven by the recognition that the absence of accidents does not imply the presence of safety; it may simply indicate the presence of luck.

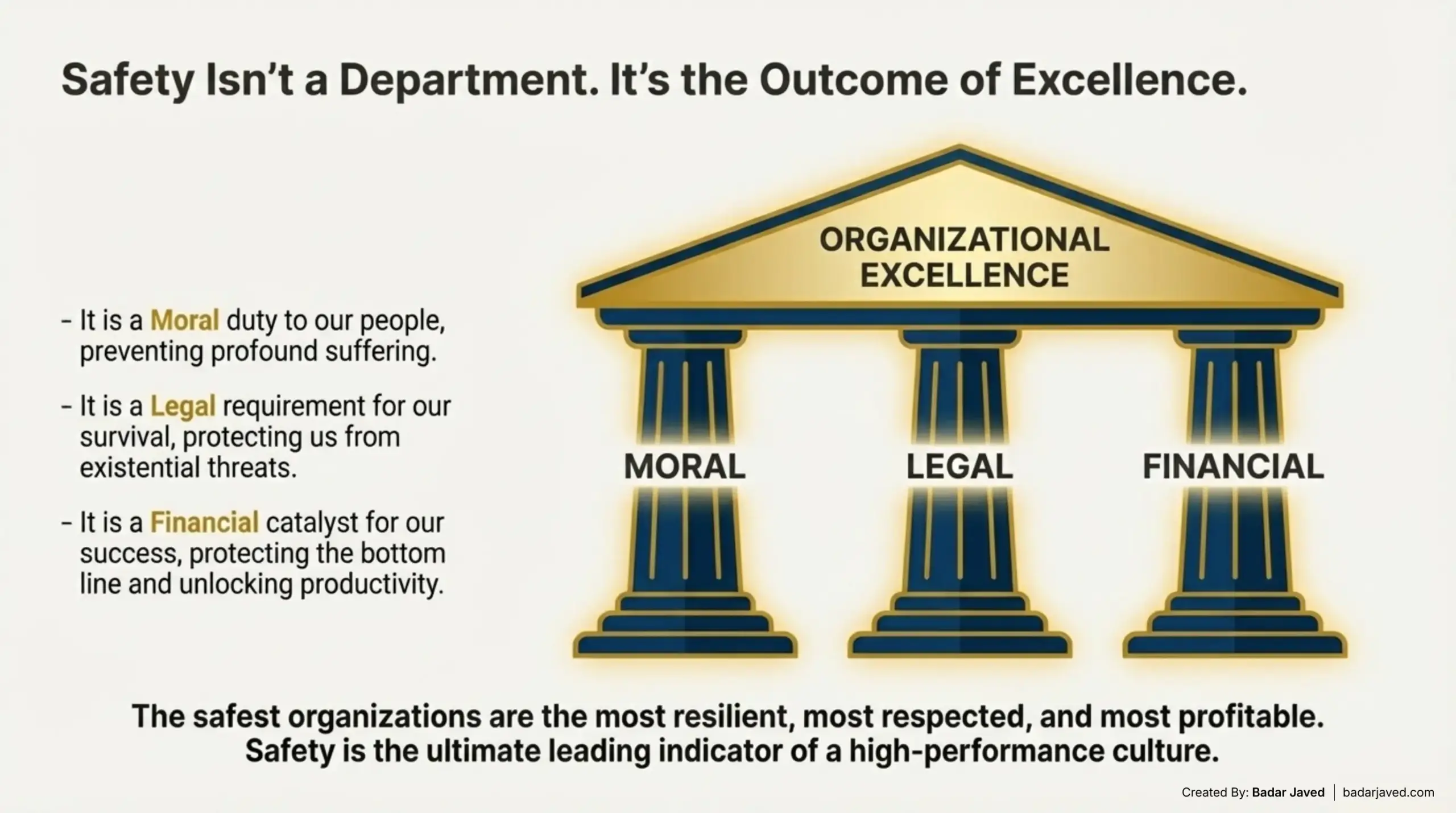

The Tripartite Framework

To understand the “why” of safety management, one must examine the three distinct yet interconnected rationales that underpin the discipline. These are universally recognized as the Moral, Legal, and Financial arguments.

- The Moral Argument: Focuses on the humanitarian obligation to prevent suffering and the ethical imperative that work should not harm the worker.

- The Legal Argument: Focuses on the statutory obligations imposed by society through legislation, and the criminal or civil penalties for non-compliance.

- The Financial Argument: Focuses on the economic reality that accidents are essentially operational errors that destroy value, while safety is an investment that protects assets and enhances efficiency.

This report will explore each of these pillars in depth, supported by historical context, legal precedent, and economic data, to provide a holistic view of the strategic necessity of OHS.

The Moral Imperative: The Ethics of Human Capital

The moral reason for managing health and safety is the most fundamental. It exists independently of profit margins or government decrees. It is rooted in the intrinsic value of human life and the societal expectation that organizations act as responsible stewards of the people under their employ.

1. The Duty of Care and Human Dignity

The concept of “Duty of Care” is central to the moral argument. It posits that employers have an ethical obligation to ensure that their operations do not cause harm to employees, contractors, visitors, or the public. This duty arises from the power dynamic inherent in employment: the employer controls the workplace, the equipment, and the processes; therefore, the employer bears the responsibility for the risks generated by those elements.

The Right to Safe Return

There is a universal, unwritten contract between employer and employee: the worker trades their labor and time for wages, not for their health or life. A responsible employer recognizes that every employee has a right to return home at the end of the shift in the same physical and mental condition in which they arrived. This moral duty extends to the prevention of pain, suffering, and the long-term impacts of occupational disease, which may not manifest until years after employment has ceased.

The Societal Ripple Effect

Workplace accidents do not occur in a vacuum. The moral weight of an injury or fatality is amplified by its impact on the victim’s family, dependents, and community.

- Family Impact: The loss of a breadwinner can plunge a family into poverty. Even non-fatal injuries can lead to loss of income, strain on family relationships, and long-term care burdens.

- Psychological Trauma: Case studies from Ireland highlight that the aftermath of workplace accidents includes deep psychological scars such as depression, anxiety, feelings of isolation, and embarrassment. The injured worker may feel resentment toward the employer, while colleagues may suffer from “survivor’s guilt” or fear for their own safety.

- Community Trust: Organizations are part of the social fabric. A company that repeatedly injures its workers violates the trust of the community in which it operates. This breach of trust is viewed as a moral failing, distinguishing “predatory” capitalism from responsible enterprise.

2. Historical Catastrophes and the Moral Awakening

The moral imperative has been sharpened over the last century by a series of industrial disasters that exposed the consequences of prioritizing profit over human life. These events serve as grim milestones in the evolution of safety ethics.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire (1911)

Perhaps the most pivotal event in US labor history, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City resulted in the deaths of 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrant women. The tragedy was not an “accident” in the true sense; it was the result of deliberate negligence. Management had locked the exit doors to prevent theft and unauthorized breaks. When the fire broke out in a scrap bin, workers were trapped. The fire escape collapsed under the weight of fleeing employees, and firefighters’ ladders were too short to reach the upper floors. The sight of women jumping to their deaths to escape the flames galvanized the public and led to the realization that the free market alone would not protect workers—a moral intervention was required.

The Monongah Mining Disaster (1907)

Occurring just years before the Triangle fire, this disaster in West Virginia remains the worst mining accident in US history. An explosion ripped through the Fairmont Coal Company mines, killing at least 362 men and boys. The disaster highlighted the expendability of labor in the early 20th century, particularly immigrant labor. The moral outrage following Monongah contributed to the creation of the US Bureau of Mines, acknowledging that the government had a moral duty to intervene in hazardous industries.

The Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster (1930s)

During the construction of a tunnel in West Virginia, thousands of workers were exposed to high levels of silica dust. Without proper respiratory protection, hundreds died from acute silicosis. The tragedy was compounded by the fact that the company knew the risks but chose to ignore them to speed up construction. This event stands as a stark example of the moral depravity that can occur when economic incentives are unchecked by ethical considerations.

3. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Reputation

In the modern era, the moral imperative is often codified in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policies. Stakeholders—including investors, customers, and potential employees—evaluate companies based on their ethical treatment of workers.

- Reputation Management: In the digital age, news of safety breaches spreads instantly. A reputation for poor safety is a reputation for poor management and low moral standards. This can lead to consumer boycotts and the loss of “social license to operate”.

- Talent Attraction: High-quality candidates prefer employers who value their well-being. A strong safety culture acts as a signal of a benevolent and professional organizational culture, making recruitment easier and less costly.

The Legal Imperative: Compliance, Liability, and Punishment

While the moral argument appeals to conscience, the legal argument appeals to the necessity of survival. Governments impose laws to ensure that the moral duty of care is not optional. The legal framework provides a floor for safety standards, below which no organization is permitted to operate.

1. The Global and National Regulatory Landscape

The legal architecture of health and safety is derived from both international conventions and national statutes.

International Labor Organization (ILO)

The ILO sets global standards that influence national legislation. These conventions establish fundamental rights, such as the right to a safe work environment, the right to information about hazards, and the right to refuse unsafe work. Most countries base their domestic laws on these principles.

The United Kingdom: Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974

In the UK, the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (HSWA) is the primary legislation. It is an “enabling act” that allows for specific regulations (like COSHH for hazardous substances or RIDDOR for reporting injuries) to be created under its umbrella.

- The Concept of “Reasonably Practicable”: The UK law requires employers to ensure safety “so far as is reasonably practicable.” This legal term implies a balance between the level of risk and the cost (in money, time, and trouble) of mitigating it. However, if the risk is high, the cost of mitigation must be grossly disproportionate to be considered a valid reason for non-implementation.

The United States: Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970

The OSH Act created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and established the “General Duty Clause,” which requires employers to provide a workplace “free from recognized hazards.” Unlike the goal-setting nature of some UK law, OSHA often relies on specific, prescriptive standards for different industries (construction, general industry, maritime).

2. Criminal vs. Civil Liability

Legal responsibility generally falls into two categories: criminal and civil. Understanding the distinction is vital for management.

Criminal Liability (Punishment)

Criminal law deals with offenses against the state. Regulatory bodies (like the HSE in the UK or OSHA in the US) prosecute companies or individuals for breaking safety laws.

- Fines: Penalties for safety violations can be substantial. In the US, “willful” violations can result in fines of hundreds of thousands of dollars per incident. In the UK, fines for corporate manslaughter are unlimited and are intended to be punitive enough to impact shareholders.

- Imprisonment: In cases of gross negligence, individual directors and managers can face prison sentences. This personal liability pierces the corporate veil, meaning a manager cannot hide behind the company’s legal entity if they were personally responsible for a safety failure.

- Enforcement Notices: Inspectors have the power to issue notices that stop work immediately (Prohibition Notice) or require improvements by a certain date (Improvement Notice). A stop-work order on a critical project can cost millions in delays.

Civil Liability (Compensation)

Civil law deals with disputes between individuals. An injured worker can sue their employer for compensation.

- Tort of Negligence: To succeed in a claim, the employee must prove that the employer owed a duty of care, breached that duty, and that the breach caused the injury.

- Vicarious Liability: Employers are generally liable for the negligent acts of their employees committed in the course of employment. If an employee drives a forklift recklessly and injures a colleague, the company is liable for the damages.

- Workers’ Compensation: In many jurisdictions (like the US), a “no-fault” insurance system exists where workers give up the right to sue in exchange for guaranteed compensation for medical bills and lost wages. However, this does not cover all costs, and exceptions exist for “intentional torts”.

3. Specific Regulatory Mechanisms

Specific regulations address particular hazards, creating a complex web of compliance requirements:

- RIDDOR (UK): The Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations requires employers to report specific serious accidents. Failure to report is a crime in itself.

- COSHH (UK): The Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations mandates risk assessments for chemical and biological agents.

- ISO 45001: While voluntary, this international standard helps organizations prove they have a robust management system, which can be a defense in legal proceedings by demonstrating “due diligence”.

The Financial Imperative: The Economics of Safety

The financial argument is often the most persuasive for executive leadership. It counters the misconception that safety is a net cost. In reality, safety is a form of loss control. Accidents are operational errors that result in waste, inefficiency, and direct financial loss.

Table: The Cost of Safety vs. The Cost of Accidents:

| Category | Direct Costs (Insured) | Indirect Costs (Uninsured) |

| Examples | Medical bills, Workers’ Comp, Legal fees | Lost productivity, Training replacements, Investigation time, Reputation damage |

| Magnitude | $1 (The Tip) | $4 – $10 (The Iceberg) |

| Financial Impact | Covered by premiums (initially) | Paid directly from profit margins |

1. The Iceberg Theory of Accident Costs

A central concept in safety economics is the “Iceberg Theory.” This analogy illustrates that the visible, insured costs of an accident are merely the “tip of the iceberg,” while the massive bulk of uninsured costs lies hidden beneath the surface.

Direct Costs (The Tip)

These are the costs that are easily quantifiable and usually covered by insurance.

- Medical Expenses: Ambulance, hospital, and rehabilitation bills.

- Compensation Payments: Wages paid to the injured worker while they are off work.

- Legal Fees: Costs associated with defending against claims.

- Regulatory Fines: Penalties paid to government bodies.

- Statistics: In 2018, serious non-fatal workplace injuries in the US amounted to nearly $59 billion in direct workers’ compensation costs alone.

Indirect Costs (The Submerged Mass)

Indirect costs are uninsured and paid directly from the company’s profits. These can be 4 to 10 times greater than direct costs.

- Lost Productivity: When an accident occurs, work stops. The injured worker is lost, but so is the time of colleagues who stop to help or watch, and the time of supervisors who must reorganize the work.

- Investigation Time: Managers, safety officers, and engineers spend countless hours investigating the root cause, writing reports, and meeting with inspectors. This is time diverted from revenue-generating activities.

- Replacement and Training: Hiring a temporary worker or training a permanent replacement is expensive. New workers are also less productive and more likely to have accidents themselves, creating a vicious cycle.

- Equipment and Product Damage: Accidents often involve damage to machinery, tools, or the product itself. A forklift crash might injure a driver (direct cost) but also destroy a pallet of expensive goods and wreck the forklift (indirect cost).

- Insurance Premiums: Insurance is based on risk. A company with a high frequency of accidents will see its “Experience Modification Rate” (EMR) rise, leading to significantly higher premiums for years to come.

- Reputation and Contracts: Clients in high-risk industries (like oil and gas) will not hire contractors with poor safety records. A bad safety record can disqualify a company from bidding on lucrative government contracts.

2. Return on Investment (ROI) of Safety

Investing in safety creates positive financial returns. Research consistently shows that safety programs pay for themselves.

- The Multiplier Effect: Studies indicate that for every $1 invested in injury prevention, businesses see a return of $2 to $6.

- National Impact: The National Safety Council estimated that work-related deaths and injuries cost the US economy $171 billion in 2019. Reducing this burden frees up capital for innovation and growth.

- Stock Market Performance: Investors increasingly use safety data as a screening tool. A study found that between 2004 and 2007, investors could have increased their returns by at least four percentage points by screening out companies with poor safety oversight.

Table: Return on Investment (ROI) Statistics:

| Metric | Value |

| ROI Ratio | $1 invested yields $2 – $6 return |

| Stock Performance | Safer companies outperformed market by >4% |

| Injury Cost (US) | $171 Billion (2019 Total Cost) |

| Injury Rate w/ Poor Psych Safety | 36.5% (vs 20.2% in safe environments) |

3. The Alcoa Case Study: Safety as a Proxy for Efficiency

The tenure of Paul O’Neill at Alcoa (Aluminum Company of America) is the definitive case study for the financial value of safety.

- The Strategy: When O’Neill became CEO in 1987, he shocked Wall Street by declaring his primary goal was not profit, but zero injuries. He reasoned that you cannot have a high-quality, low-cost production process if you do not have control over your operations. Accidents were proof of a lack of control.

- The Mechanism: O’Neill democratized safety. He gave every worker the authority to stop the line if they saw a safety issue. He required that any injury be reported to him personally within 24 hours, along with a solution. This forced management to fix problems immediately.

- The Result: The focus on safety forced improvements in process, maintenance, and communication. These improvements naturally led to higher quality and efficiency. Over his tenure, Alcoa’s injury rate dropped to 5% of the US average, while its market capitalization grew from $3 billion to $27 billion.

Organizational Benefits: Human Capital and Resilience

Beyond the “Big Three” drivers, managing health and safety delivers critical benefits to organizational culture, human resources, and operational resilience.

1. Employee Retention, Recruitment, and Morale

In the “war for talent,” safety is a decisive factor.

- The Psychological Contract: Employees today expect more than just a paycheck; they expect a duty of care. Research shows that 61% of workers said they would work harder for an employer who invested in their health.

- Retention: High turnover is a massive hidden cost. Employees who feel unsafe are more likely to leave. Conversely, a strong safety climate increases job satisfaction and loyalty. In the trucking industry, drivers with positive perceptions of safety climate were significantly less likely to quit.

- Recruitment: Top talent avoids companies with “toxic” or unsafe reputations. A survey by SHRM found that company culture (of which safety is a key dimension) is the number one reason candidates choose a job.

- Morale: A safe workplace is a morale booster. When employees see management investing in their safety—fixing a broken step, providing better PPE—they feel valued. This validation increases engagement and productivity.

2. Operational Resilience and Business Continuity

Safety management systems are essentially risk management systems. The same protocols that prevent accidents also prevent other operational disruptions.

- Crisis Readiness: Companies with robust safety cultures have established emergency plans, communication chains, and incident command structures. When a natural disaster or external crisis hits, these companies can pivot and respond faster than their competitors.

- Avoiding Bottlenecks: Accidents interrupt the flow of work. By preventing accidents, companies ensure “uptime” and reliability, which is crucial for Just-In-Time (JIT) supply chains.

3. Innovation and Quality

There is a direct link between safety and quality. Both require adherence to standard operating procedures (SOPs) and a “zero defect” mentality.

- Worker Participation: Safe workplaces encourage workers to speak up. The same channel used to report a safety hazard can be used to report a quality defect or suggest a process improvement. This “bottom-up” flow of information is vital for innovation.

- Precision: Safe work is often precise work. The discipline required to lock out a machine or handle hazardous chemicals safely translates into the discipline required to manufacture high-tolerance products.

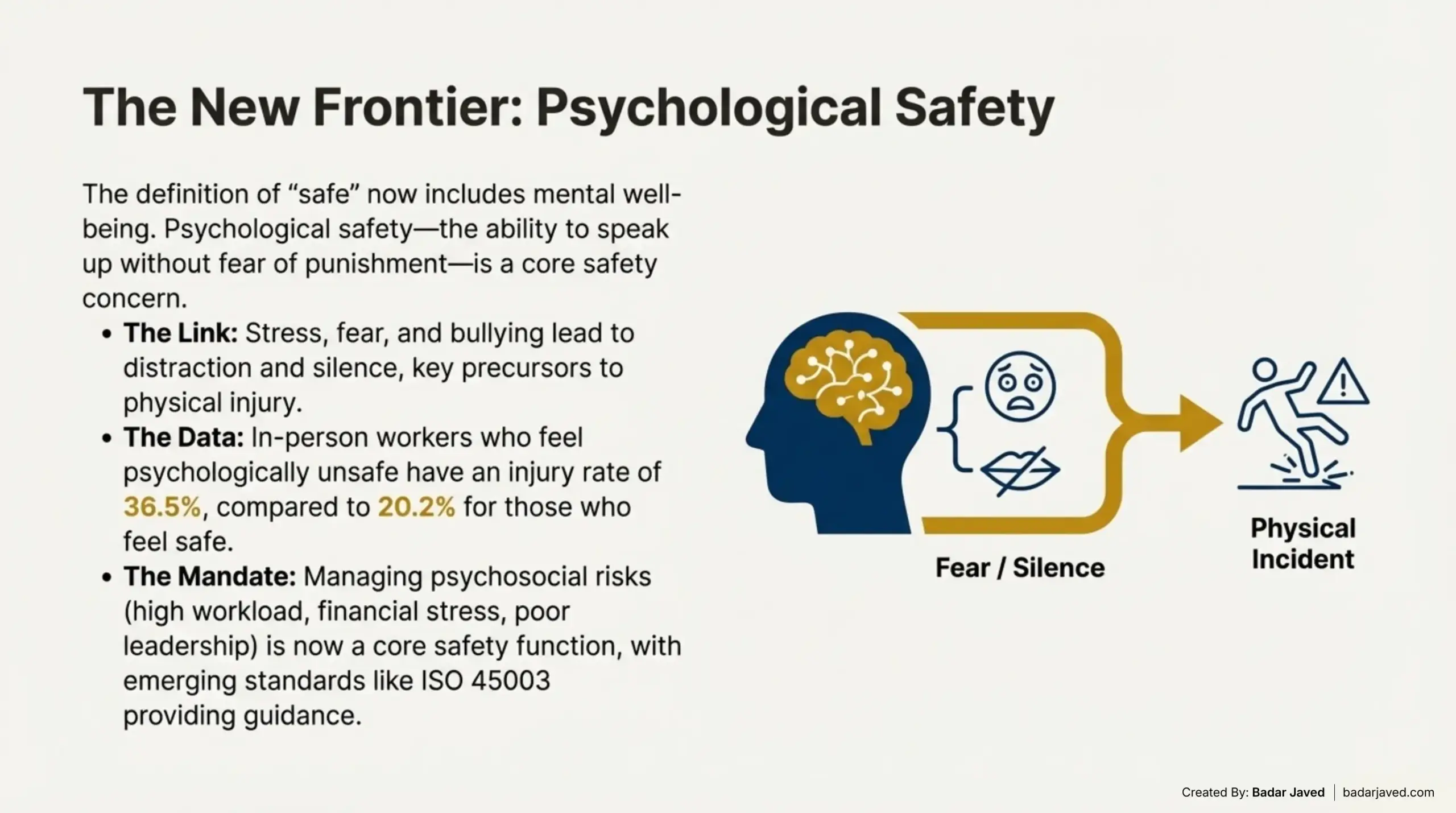

Psychological Safety: The New Frontier

The definition of “health and safety” has expanded significantly in recent years to encompass mental health and “psychological safety.” This is no longer a peripheral “wellness” issue but a core safety concern.

1. The Connection Between Psychological and Physical Safety

There is a proven correlation between how safe employees feel psychologically and how safe they are physically.

- The Distraction Factor: An employee who is stressed, bullied, or fearful of retribution is a distracted employee. In high-risk environments, distraction kills.

- The Silence Factor: “Psychological safety” is defined as the ability to speak up without fear of punishment. If a worker is afraid to report a near-miss or a hazard because they fear being blamed, the hazard remains.

- The Data: Research indicates that workers who feel their employer discourages reporting are 2.4 times more likely to experience a work injury. Another study found that in-person workers who felt psychologically unsafe had an injury rate of 36.5%, compared to 20.2% for those who felt safe.

2. Managing Psychosocial Risks

The new frontier of safety management involves identifying and mitigating “psychosocial hazards.”

- Contributing Factors: Dräger’s research identifies key contributors to a lack of psychological safety: high workload/time pressures (48%), financial stress (42%), and lack of supportive leadership (30%).

- ISO 45003: This is the first global standard giving practical guidance on managing psychological health. It emphasizes that mental health is a management system issue, not just an individual HR issue. It requires assessing risks like poor communication, lack of autonomy, and workplace harassment.

- Demographic Concerns: The concern over psychological safety is highest among Millennials (70%) and managers (71%), indicating that the future workforce and current leadership are acutely aware of this risk.

Strategic Implementation: Standards and Culture

Knowing why to manage safety is the first step; knowing how is the second. Successful organizations implement robust management systems and foster a positive safety culture.

1. ISO 45001: The Global Standard

ISO 45001 is the international standard for Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems (OHSMS). It provides a framework for organizations to proactively improve safety performance.

- Benefits of Certification: Implementing ISO 45001 helps organizations identify risks, comply with legislation, and demonstrate “due diligence” to stakeholders. It is often a requirement for international trade.

- Structure: It follows the “Plan-Do-Check-Act” (PDCA) cycle and integrates with other standards like ISO 9001 (Quality) and ISO 14001 (Environment). This integration ensures that safety is not a siloed activity but part of the overall business management system.

2. Safety Culture and Leadership

Safety culture is “the way we do things around here.” It is the shared values and beliefs that drive behavior when no one is watching.

- Leadership Visibility: Culture is set from the top. Leaders must be visible champions of safety. If a CEO walks past a hazard without acting, they have just set a new, lower standard for the entire company.

- Empowerment: Case studies from companies like Dalkia Energy Solutions and Texas Roadhouse show that empowering employees is key. Dalkia uses the term “zero harm” and focuses on inclusion and empowerment. Texas Roadhouse integrates safety into their mission of “Legendary Service,” empowering staff to ensure guests feel safe.

- Moss Construction Approach: Their advice for improving culture is simple: “Go to the front line and ask the workers.” The workers know where the risks are. Listening to them is the fastest way to improve culture.

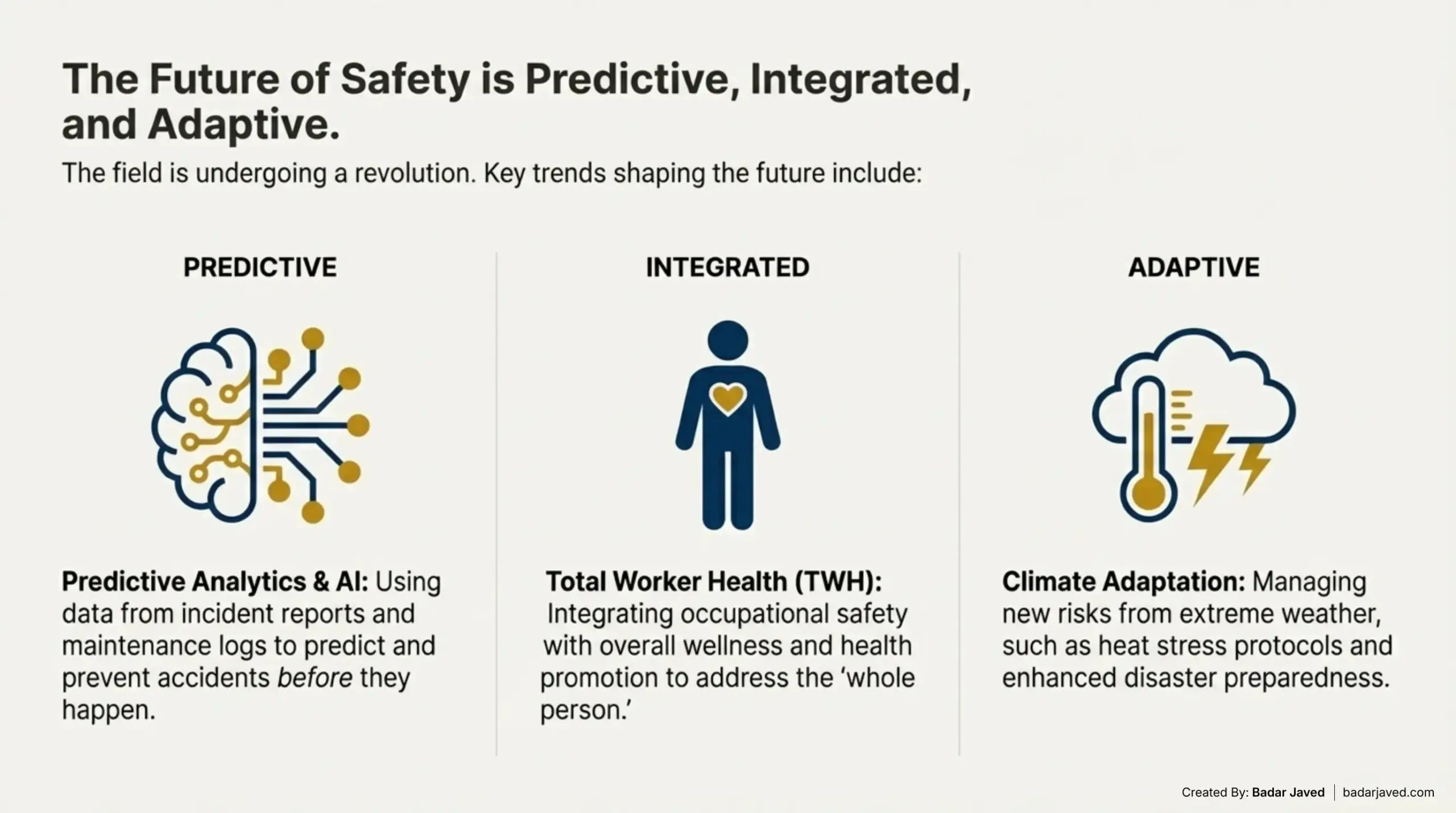

Future Trends: The Evolution of Safety (2025 and Beyond)

The field of health and safety is undergoing a technological and conceptual revolution. As we look toward 2025, several key trends are shaping the future of the discipline.

Table: Evolution of Safety Milestones:

| Year | Event/Legislation | Impact |

| 1911 | Triangle Shirtwaist Fire | Catalyzed US labor unions and fire codes |

| 1970 | US OSH Act | Created OSHA; established federal safety standards |

| 1974 | UK HSWA | Established “Duty of Care” and “Reasonably Practicable” |

| 1987 | Paul O’Neill at Alcoa | Proved safety drives stock value ($3B -> $27B) |

| 2018 | ISO 45001 | Global standard for OHS management systems |

1. Technology and AI

Technology is shifting safety from reactive to predictive.

- Predictive Analytics: AI is being used to analyze vast amounts of data (incident reports, observations, maintenance logs) to predict where the next accident is likely to occur. This allows managers to intervene before an incident happens.

- Wearable Technology: Smart PPE is becoming standard. Vests can detect if a worker is overheating, helmets can detect fatigue or lack of movement (man-down), and proximity sensors can warn workers if they are too close to heavy machinery.

- AI-Powered Mental Health: AI chatbots and virtual companions are emerging as scalable tools to provide mental health support, offering immediate assistance for stress and anxiety, though ethical guardrails remain a concern.

2. Total Worker Health (TWH)

The concept of “Total Worker Health,” championed by NIOSH, is gaining traction. It recognizes the link between work-related factors and non-work-related health. For example, a worker who is obese or has diabetes may be at higher risk for musculoskeletal injury. TWH programs integrate occupational safety with health promotion, addressing the “whole person” rather than just the “worker”.

3. Climate-Driven Safety

As climate change leads to more extreme weather events, safety management must adapt. This includes new protocols for heat stress management, working in extreme storms, and disaster preparedness for facilities located in vulnerable areas.

Table: Key Terminology

Term | Definition | Context |

|---|---|---|

Duty of Care | The legal/moral obligation to ensure safety of others. | Foundation of all safety law. |

Vicarious Liability | Employer liability for employee actions. | Why companies pay for worker negligence. |

Psychological Safety | Ability to speak up without fear of retribution. | Critical for preventing hidden errors. |

Leading Indicators | Proactive metrics (e.g., audits, near-misses). | Predicting accidents before they happen. |

Iceberg Theory | Indirect costs exceed direct costs. | Economic justification for safety. |

Conclusion

The management of health and safety is not a peripheral administrative task; it is a fundamental strategic imperative that lies at the heart of organizational success. The reasons for managing health and safety are robust and multifaceted:

- Morally, it affirms the value of human life and fulfills the ethical duty of care that civilized society demands. It prevents the profound suffering of workers and their families.

- Legally, it ensures compliance with rigorous international and national statutes, protecting the organization and its leadership from criminal prosecution, civil liability, and existential regulatory threats.

- Financially, it protects the bottom line by preventing the massive hidden costs of accidents, lowering insurance premiums, and unlocking the productivity gains associated with operational control.

Beyond these primary drivers, a robust safety culture acts as a catalyst for employee engagement, operational resilience, and innovation. As demonstrated by industry leaders like Alcoa, and reinforced by modern standards like ISO 45001, safety is a proxy for excellence. In an era of increasing complexity, technological change, and social scrutiny, the organizations that thrive will be those that recognize that safety is not a cost to be managed, but an investment to be maximized. The future of business belongs to those who keep their people safe.