I was recently auditing a large logistics terminal that had just transitioned its entire forklift fleet to lithium-ion batteries. During the walk-through, I asked the warehouse manager what their response plan was if one of the charging banks went into thermal runaway. He pointed to a standard dry powder extinguisher and said, “We’d just treat it like an electrical fire.” I had to stop the audit right there. I explained that if a 48V battery pack breaches, that powder extinguisher would be as effective as a water pistol against a volcano. The jet-like flames and toxic off-gassing from a battery failure don’t follow the rules of ordinary combustible fires.

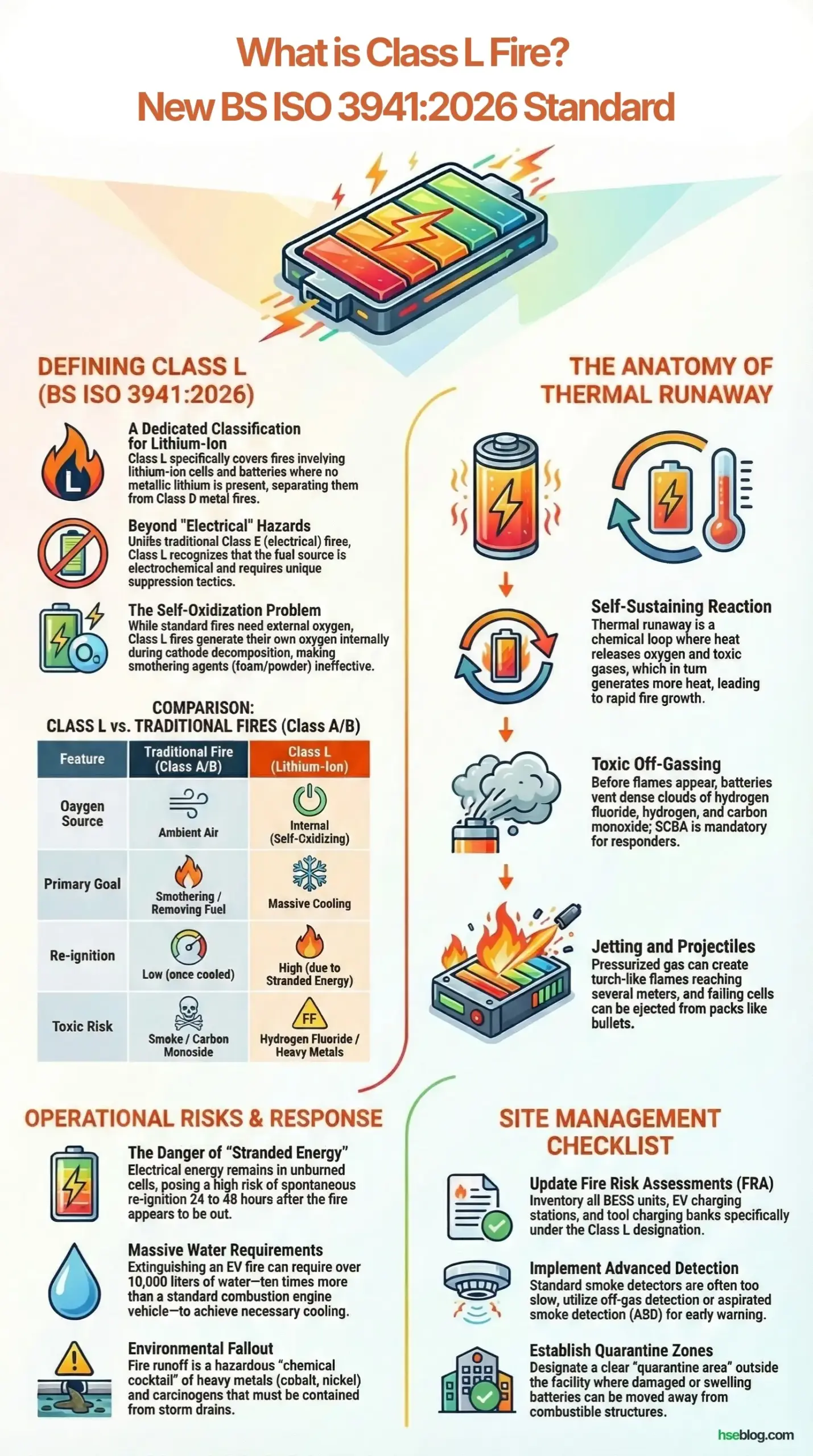

This is exactly why the safety industry has shifted. With the publication of BS ISO 3941:2026, we finally have a formal designation for this hazard: Class L. This isn’t just a paperwork change; it is a critical recognition that lithium-ion battery fires possess unique electrochemical behaviors—extreme heat release, explosive gas venting, and self-oxygenation—that distinct them from Class A, B, or traditional electrical fires. If you are managing a site with energy storage, EVs, or even heavy power tool usage, understanding Class L is now a fundamental part of your duty of care.

TL;DR: Executive Summary for Field Operations

- Definition: Class L is the newly standardized fire classification (BS ISO 3941:2026) specifically for lithium-ion cells and batteries where no metallic lithium is present.

- The Mechanism: Unlike standard fires, Class L fires are driven by “thermal runaway”—a self-sustaining chemical reaction that releases oxygen, heat, and toxic gases internally.

- Extinguishing Challenge: Traditional smothering agents (foam/powder) often fail because the fire generates its own oxygen; massive cooling is required to stop propagation.

- Re-ignition Risk: “Stranded energy” remains inside damaged cells, meaning fires can spontaneously reignite hours or days after apparent extinguishment.

- Immediate Action: Update your site Fire Risk Assessments (FRA) to specifically inventory BESS units, EV charging stations, and tool charging banks under this new class.

Defining Class L: Beyond Standard Fire Classes

Class L is the new category defined by BS ISO 3941:2026 Classification of fires, covering fires involving lithium-ion cells and batteries where no metallic lithium is present. This distinction is crucial for field practitioners because it separates modern rechargeable batteries from the combustible metal fires (Class D) we dealt with in older chemical processing contexts.

In my experience, the industry has struggled for years to shoehorn battery fires into existing categories. We used to treat them as Class E (electrical) initially, then Class B (flammable liquid) due to the electrolyte. Neither was accurate. Class L acknowledges that the fuel source is electrochemical and the hazard profile is fundamentally different.

The Core Characteristics of Class L

- Self-Oxidizing: The cathode material in decomposing batteries releases oxygen, fueling the fire even if you smother it.

- Rapid Growth: A failure in a single cell can heat adjacent cells to failure points within seconds.

- Toxic Venting: Before flames appear, these batteries release dense clouds of hydrogen fluoride, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide.

The “Thermal Runaway” Factor

To understand Class L, you must understand thermal runaway. In standard fires, you remove heat, fuel, or oxygen to break the triangle. in a Class L fire, the battery internalizes the fire triangle.

I once investigated a near-miss at a renewable energy site where a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) module failed. The operator described a “popping sound” followed by a jet of white gas that ignited instantly. This wasn’t a slow burn; it was an energetic release.

Why Class L Behaves Differently

- Propagation: Heat transfers from cell to cell. You might extinguish the external flame, but the reaction is moving deeper into the battery pack.

- Jetting: Pressurized gas builds up inside the casing until it vents violently, creating torch-like flames that can reach several meters.

- Explosion Risk: If the vented gases accumulate in a confined room (like a charging container) without igniting immediately, a spark can cause a catastrophic volumetric explosion.

Operational Risks and Re-ignition

The most dangerous aspect of a Class L fire for emergency responders and site safety managers is Stranded Energy. This is the electrical energy remaining in the battery cells that haven’t yet burned.

In a traditional Class A fire (wood/paper), once the water hits it and the steam clears, the fire is usually out. In Class L scenarios, I have seen battery packs reignite 24 to 48 hours after the incident. The damaged cells can short-circuit internally, heating up again without warning.

Key Risks for Responders

- Toxic Toxicity: The smoke contains Hydrogen Fluoride (HF), which is highly corrosive to skin and lungs. Standard filtration masks are often insufficient; SCBA is mandatory.

- Projectiles: As cells over-pressure, they can be ejected from the battery pack like bullets, spreading fire to adjacent racks or vehicles.

- Electric Shock: Fire water becomes conductive when mixed with the exposed electrolytes and high-voltage busbars.

Practical Implications for Fire Risk Assessment (FRA)

With the introduction of Class L, your existing Fire Risk Assessment is likely outdated if you have significant battery assets. As an auditor, if I see a “generic” fire plan for a room full of Li-ion batteries, I mark it as a non-conformance.

You must identify where Class L hazards exist. It is no longer acceptable to group these with general electrical hazards.

Assessment Checklist for Class L

| Assessment Area | What to Look For |

| Inventory | Total kWh capacity on site (BESS, EV chargers, forklift bays). |

| Separation | Are charging areas fire-separated from main combustible loads (pallets, packaging)? |

| Detection | Standard smoke detectors are too slow. You need off-gas detection or aspirated smoke detection (ASD). |

| Suppression | Is the suppression system designed to cool? Gas suppression (clean agent) may suppress the flame but won’t stop the thermal runaway heating. |

Pro Tip: For warehouse charging bays, ensure there is a clear “quarantine area” outside. If a battery shows signs of heating or damage (swelling/smell), you need a safe path to move it outdoors immediately, away from the building structure.

Suppression and Control Strategies

Combating a Class L fire requires a shift in tactics. The objective changes from “extinguishing” to “cooling and containment.”

Water is King (For Cooling)

Despite the electrical hazard, water is currently the most effective agent for Class L fires because of its high heat absorption capacity. However, the volume required is immense.

- Volume: Extinguishing an EV fire can take 10,000+ liters of water, compared to 1,000 liters for a combustion engine car.

- Application: Water must be applied directly to the battery casing for a prolonged period to soak away the heat generated by the chemical reaction.

Specialized Agents

There are emerging agents specifically for Class L, such as vermiculite-based dispersions or encapsulating agents. These form a thermal barrier to stop propagation.

- Fire Blankets: High-temperature fire blankets are effective for containment. They won’t put the fire out (because the battery makes its own oxygen), but they prevent the flames from igniting the warehouse roof or adjacent cars.

Clean-Up and Environmental Impact

The runoff from a Class L fire is a hazardous chemical cocktail.

- Heavy Metals: Cobalt, nickel, and manganese leach into the water.

- Carcinogens: The runoff is strictly hazardous waste. You cannot wash this down the storm drain. As an Environmental Specialist, I always ensure spill kits and drain covers are deployed before firefighting begins if safe to do so.

Conclusion

The introduction of Class L in BS ISO 3941:2026 is a necessary evolution of safety standards in an electrified world. It validates what we in the field have known for years: lithium-ion batteries are not just another fuel source; they are complex energy storage devices that demand respect.

For safety professionals, the “put wet stuff on the red stuff” mentality is dangerous here. You must update your training, your risk assessments, and your emergency plans to account for thermal runaway, toxic off-gassing, and delayed re-ignition. When a Class L fire starts, your goal isn’t just to save the asset—it’s to prevent a catastrophic chain reaction and keep your people away from the toxic fallout. Treat these batteries with the caution they deserve.