I once watched a 28-year-old welder at a fabrication yard struggle to stand up straight after a shift. For six months, he had been welding inside a tight vessel with his neck craned at a 45-degree angle and his torso twisted. He hadn’t suffered a sudden “accident”—no fall, no slip, no struck-by. Yet, his career was effectively over because his cervical spine had fused from repetitive micro-trauma. I had to sit with him while he processed the fact that he couldn’t pick up his kids anymore without blinding pain.

That is why we need to talk about ergonomics in the field, not as a “soft safety” topic, but as a critical defense against life-altering injury. Most workers think safety is about avoiding the immediate kill—the explosion or the fall. But as an Occupational Health Specialist, I know that Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs) take out more experienced hands than almost any other hazard. This toolbox talk isn’t about posture police; it’s about mechanical preservation of the human body so you can retire with your mobility intact.

TL;DR

- It’s Not Just “Comfort”: Ergonomics is about preventing permanent Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs), not just making the chair softer.

- The “Power Zone” is Non-Negotiable: Keep all heavy work between the knees and shoulders; anything outside this zone multiplies the force on the spine.

- Micro-Breaks Save Joints: Holding a static posture restricts blood flow; moving or stretching for 30 seconds every hour resets the body.

- Report the “Niggle”: Pain is a lagging indicator; stiffness and discomfort are leading indicators. Report them before they become a lost-time injury.

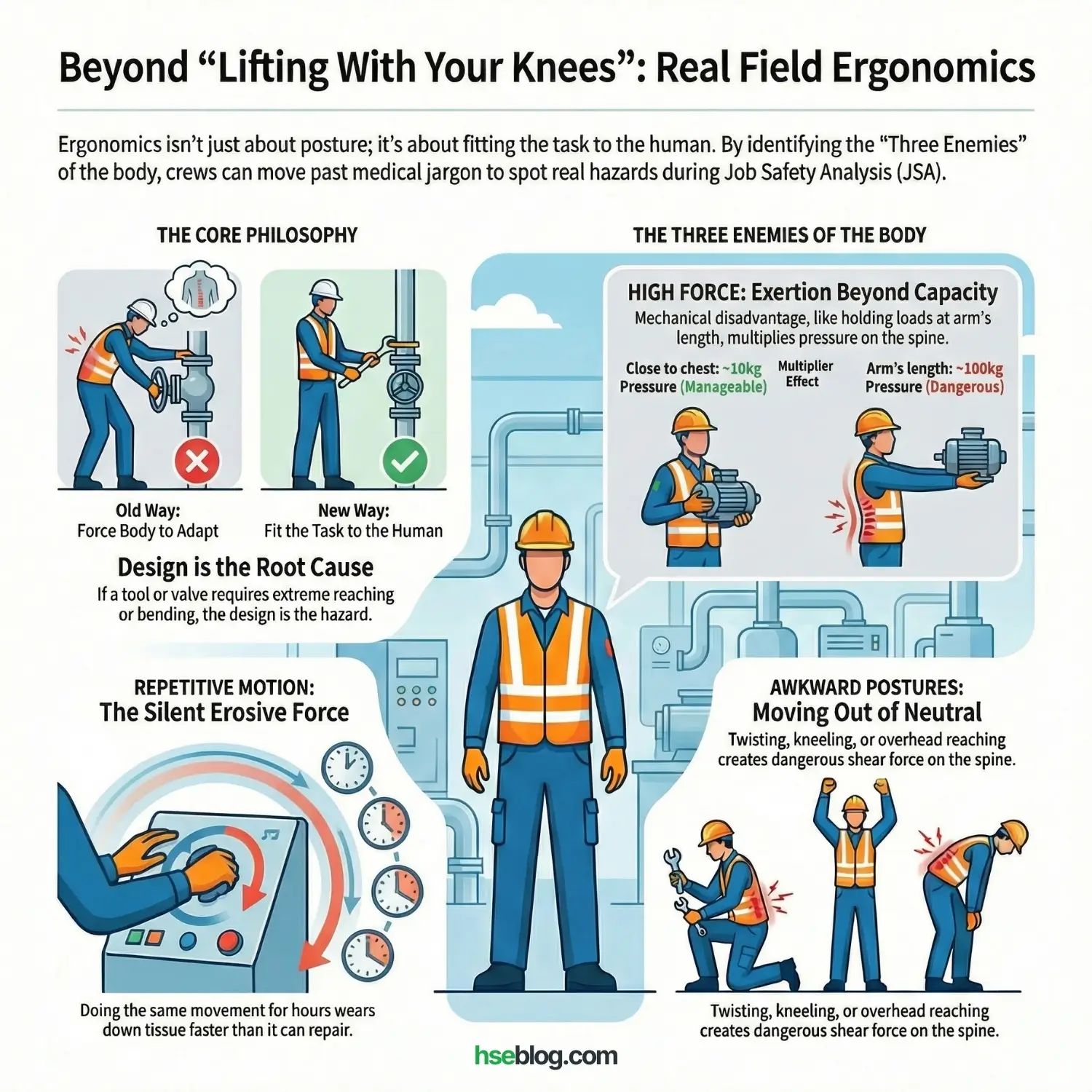

Defining Ergonomics for the Field

Too often, when I audit sites—from offshore platforms to fabrication shops—I hear supervisors define ergonomics as simply “lifting with your knees.” That is a dangerous oversimplification. It implies that if a worker squats correctly, they are immune to injury. It ignores the other 90% of the workday where they are reaching, twisting, gripping, or holding static positions.

Real field ergonomics is simply fitting the task to the human, not forcing the human to fit the task.

In operational terms, this means designing the workspace so the body stays in a neutral, strong position. When we force the body to work in unnatural positions, apply excessive force, or repeat the same motion thousands of times without recovery, we are mechanically degrading the joints and soft tissues. This isn’t about comfort; it’s about engineering out the friction between the worker and the machine.

Field Reality Check: If a tool requires you to bend your wrist 90 degrees to use it (like a pistol-grip drill used at chest height), the tool is the hazard, not your wrist. If a valve is placed 7 feet high requiring a ladder or overhead reach to turn, the design is the root cause, not the operator’s shoulder strength.

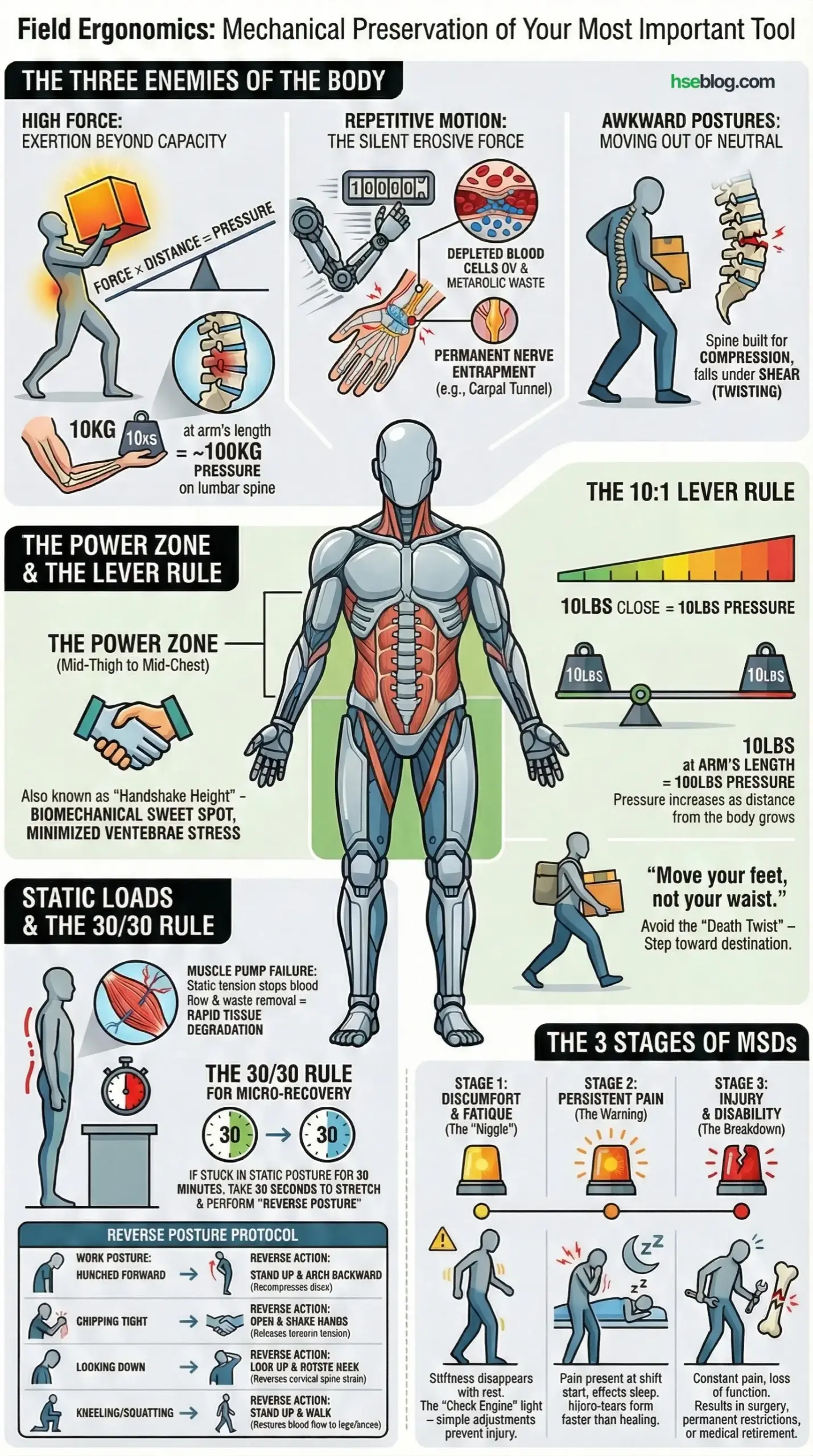

The Three Enemies of the Body

When you are delivering this talk to your crew, you need to move past medical terminology. Simplify the risk factors into these three identifiable hazards that they can spot on a Job Safety Analysis (JSA):

1. High Force: Exertion Beyond Capacity

This isn’t just about how much something weighs; it’s about the mechanical disadvantage.

- The Reality: It includes lifting, pushing, pulling, or gripping heavy loads.

- The Multiplier: Force is multiplied by distance. Holding a 10kg motor close to your chest is manageable. Holding that same 10kg motor at arm’s length to slot it into a rack places nearly 100kg of pressure on your lumbar spine due to the lever effect.

- Field Example: “Breaking” a rusted nut loose. The sudden burst of high force required often leads to torn rotator cuffs or bicep tendons if the body isn’t braced.

2. Repetitive Motion: The Silent Erosive Force

This is the most insidious hazard because it doesn’t hurt immediately. It wears down the tissue faster than the body can repair it.

- The Reality: Doing the same movement every few seconds for hours.

- The Mechanism: Repetition depletes the local blood supply to the muscles and tendons. Without rest pauses, metabolic waste (like lactic acid) accumulates, causing inflammation.

- Field Example: A steel fixer tying rebar (thousands of twists per shift) or a scaffold builder constantly turning clamps. The first 100 don’t hurt; the 10,000th causes permanent nerve entrapment (Carpal Tunnel).

3. Awkward Postures: Moving Out of Neutral

The body is strongest in a “neutral” position (spine in an S-shape, elbows at sides, wrists straight).

- The Reality: Working with hands above the head, twisting the torso, or kneeling for extended periods.

- The Danger of “The Twist”: The spine is designed to handle compression (downward force), but it is terrible at handling shear (twisting force). Twisting while carrying a load is the number one cause of disc herniation I investigate.

- Field Example: A welder working inside a pipe (confined space) with their neck craned sideways for 45 minutes, or an electrician working overhead in a drop ceiling. These postures restrict blood flow and pinch nerves.

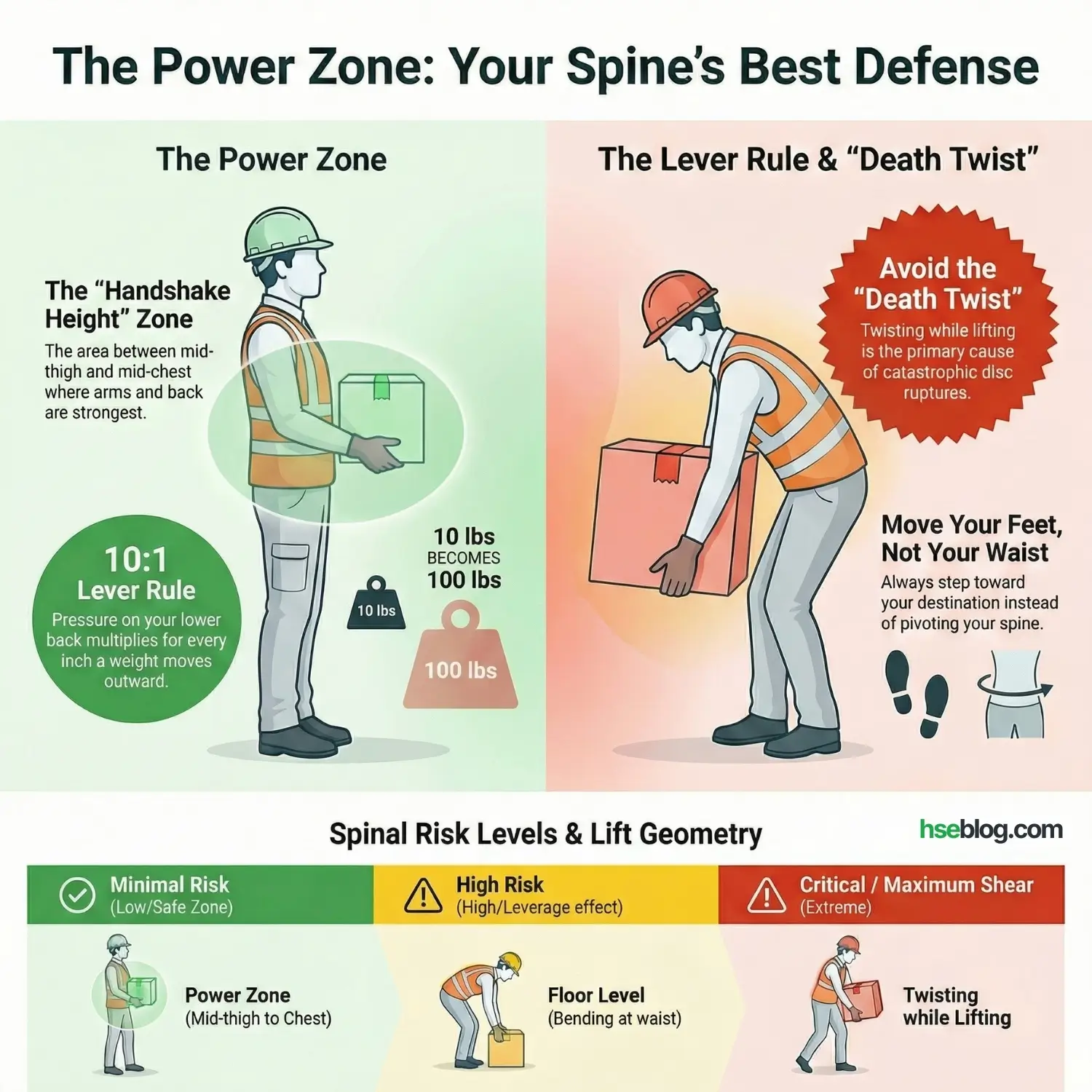

The “Power Zone” Concept

During site inspections—whether I’m walking a laydown yard or checking a warehouse—I constantly see workers lifting loads directly from the ground or reaching overhead to grab stock. They often rely on their belt or sheer muscle power to get the object moving.

This is a battle against simple physics, and it is a battle the spine will eventually lose. The rule is absolute: the further the load is from your center of gravity, the more pressure it puts on your lower back.

The most practical control you can teach your team—one that costs zero dollars—is the Power Zone.

What is the Power Zone?

Technically, it is the area between your mid-thigh and your mid-chest, kept close to the body.

Practically, I tell crews to think of it as “Handshake Height” or the “Strike Zone.” This is the biomechanical sweet spot where your arms and back are strongest. In this zone:

- Your elbows stay close to your ribs.

- Your biceps and chest do the work, rather than the smaller stabilizer muscles of the lower back.

- Lifting places the least amount of shear stress on your vertebrae.

The 10:1 Lever Rule:

When you explain this to workers, use the “Lever Rule.” For every inch you hold a weight away from your body, the pressure on your lower back multiplies.

- Holding a 10lb (4.5kg) object close to your belly button = 10lb of pressure.

- Holding that same 10lb object at arm’s length = Nearly 100lb of pressure on the L5/S1 disc.

Your spine acts as the fulcrum of a seesaw. Don’t let the load sit on the long end of the lever.

Comparison of Lifting Stress: A Field Guide

I use this comparison to show workers why “just one quick lift” from the floor is dangerous. It isn’t about the weight of the object; it’s about the geometry of the lift.

| Lift Location | Typical Site Task | Stress on Spine (L5/S1) | Risk Level |

| Power Zone (Mid-thigh to Chest) | Moving materials from a workbench to a waist-high cart. | Minimal | Low (Safe Zone) |

| Floor Level (Bending at waist) | Picking up a pump or toolbox from the ground without bending knees. | High (Leverage effect) | High |

| Overhead (Extended arms) | Racking pipes, painting ceilings, or tightening overhead valves. | Moderate + Shoulder Stress | High |

| Twisting while Lifting | Turning to load a truck or shovel gravel without moving feet. | Critical / Maximum Shear | Extreme |

The “Death Twist” (Twisting while Lifting)

You will notice in the table above that Twisting while Lifting is rated as “Extreme.” I cannot stress this enough.

The intervertebral discs in your spine are like jelly donuts. They are incredibly strong when compressed straight down (like standing up straight with a weight). However, they are incredibly weak when twisted.

When a worker picks up a load and twists their torso to place it on a pallet without moving their feet, they are grinding the vertebrae against the disc rings. This “corkscrew” action is the primary cause of the catastrophic disc ruptures I investigate.

The Fix: Teach the mantra: “Move your feet, not your waist.” If the load needs to go to the left, step to the left. Do not pivot the spine.

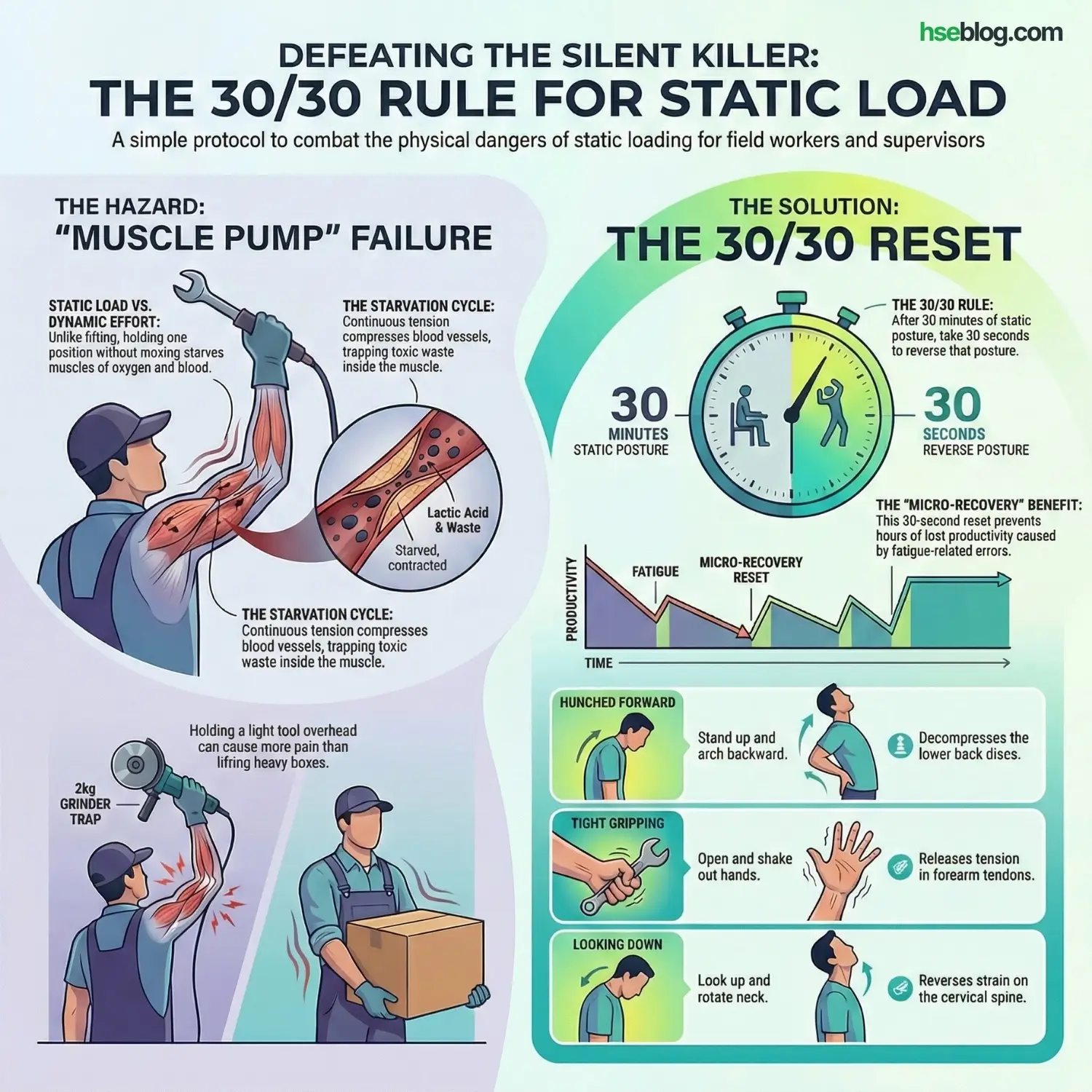

Identifying and Controlling “Static Load”

One of the most overlooked hazards I investigate is static loading. It is the silent killer of productivity and the primary cause of fatigue-related errors.

This happens when a worker holds a position for a long time without moving. Unlike lifting a heavy box (dynamic effort), static load flies under the radar. I see it constantly:

- A painter holding a brush overhead for 20 minutes.

- A mechanic leaning over an engine bay with their back flexed.

- A rigger holding a tagline taut while waiting for a crane lift.

- A welder freezing their body position to maintain a steady bead.

Why It’s Dangerous: The “Muscle Pump” Failure

To understand why this hurts, you need to understand how your body fuels itself.

Muscles rely on movement to pump blood. When you move dynamically (walking, lifting, releasing), your muscles act like a pump: they contract to squeeze old blood out and relax to let fresh, oxygen-rich blood in.

When a muscle is tensed and static, that pump stops.

- Compression: The continuous tension compresses the blood vessels.

- Starvation: Fresh blood (oxygen) cannot get into the muscle tissue.

- Toxicity: Metabolic waste (lactic acid) cannot get out.

The result is a rapid buildup of acid in the tissue. This causes the “burning” sensation you feel. If ignored, the tissue begins to fatigue, the muscle fibers physically degrade, and eventually, they fail. This is why a worker can hold a 2kg grinder overhead and feel more pain than if they lifted a 25kg box from the floor.

The 30/30 Rule for the Field

I advise crews to use the 30/30 Rule. It is easy to remember and easy to enforce.

This is not a “coffee break”; it is a “micro-recovery” essential for maintaining work quality and safety.

The Rule: If you are stuck in a static posture (kneeling, overhead reach, fixed grip) for 30 minutes, you need to take 30 seconds to stretch and reverse that posture.

For a supervisor, allowing this 30 seconds saves you hours of lost productivity later in the shift when the worker slows down due to pain.

The “Reverse Posture” Protocol

The 30 seconds must be used to perform the exact opposite of the work posture. This resets the length of the muscles and allows blood to rush back into the “starved” areas.

| If your work posture was… | Your 30-Second Reverse Action is… | Why? |

| Hunched Forward (Welding, bench work) | Stand up and arch backward. Place hands on hips and look at the sky. | Opens the chest, decompresses the discs in the lower back. |

| Gripping Tight (Grinders, drills, hammers) | Open and shake out hands. Splay fingers wide, then make a loose fist. | Releases tension in the forearm tendons (preventing tennis elbow). |

| Looking Down (Inspection, assembly) | Look up and rotate neck. Gently tuck chin and push head back. | Reverses the strain on the cervical spine (neck). |

| Kneeling / Squatting (Floor work) | Stand up and walk. | Restores blood flow to the legs and knees. |

Pro Tip for Field Leaders:

Watch your crew. If you see a guy shaking his hand out or rubbing his neck, he is already in the “Fatigue” stage. Don’t wait for him to ask for a break. Call a 30-second “Reset” for the whole team. It shows you know what you’re doing.

Early Reporting: Pain vs. Discomfort

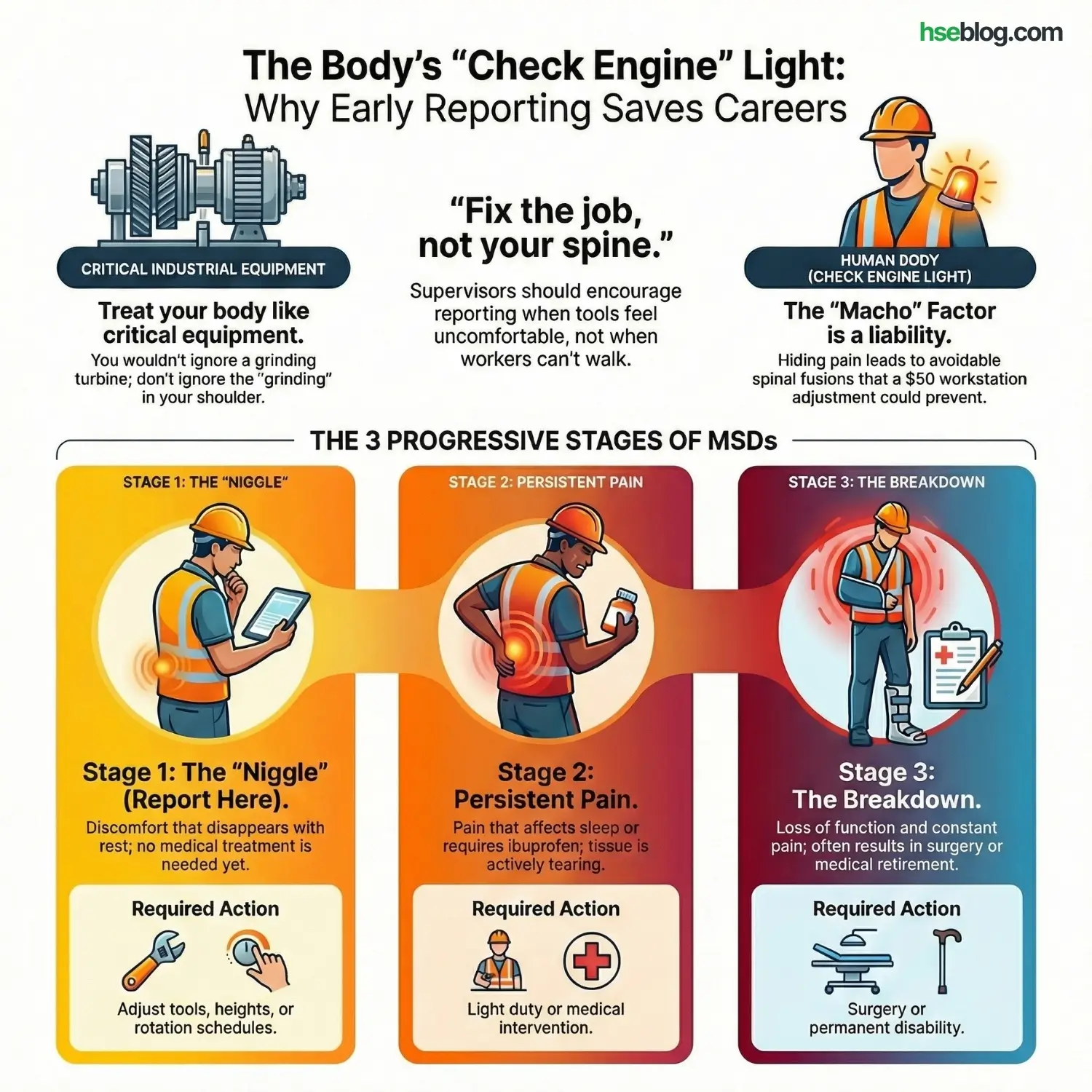

In the heavy industries I work in—construction, mining, oil & gas—there is a deep-seated cultural barrier to ergonomics: the “Macho” Factor.

Complaining about a “sore back” or a “stiff wrist” is often seen as weakness. It’s viewed as complaining. I have seen this mindset lead to spinal fusions and rotator cuff surgeries that could have been avoided with a $50 adjustment to a workstation or a $20 pair of anti-vibration gloves.

We must change the narrative on reporting. We need to treat the human body like we treat our critical equipment. You wouldn’t ignore a grinding noise in a million-dollar turbine just to “tough it out.” You shouldn’t ignore the grinding in your shoulder, either.

The Progressive Stages of MSDs

Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs) rarely happen overnight. They are cumulative. They give you warnings.

When teaching this to workers, I explain that MSDs move through three distinct stages. The goal is to catch them in Stage 1.

1. Stage 1: Discomfort & Fatigue (The “Niggle”)

- Symptoms: You feel stiffness or soreness during the shift, but the pain goes away after a night’s rest or a weekend off.

- The Reality: This is the body’s “Check Engine” light. The tissue is irritated but not damaged.

- Action: REPORT IT HERE. This is a leading indicator. At this stage, we can fix the issue by adjusting the tool, the height of the work, or the rotation schedule. No medical treatment is needed.

2. Stage 2: Persistent Pain (The Warning)

- Symptoms: The pain is there at the start of the shift. It aches on the drive home. It starts to affect your sleep. You might be taking ibuprofen just to get through the morning.

- The Reality: The tissue is now inflamed and micro-tears are forming faster than they can heal.

- Action: You are now managing an injury, not preventing one. Light duty or medical intervention is likely needed.

3. Stage 3: Injury & Disability (The Breakdown)

- Symptoms: Loss of function. You can’t grip the tool; you can’t lift your arm past your shoulder. The pain is constant, even at rest.

- The Reality: The tissue has failed. This is a lagging indicator.

- Action: Surgery, permanent restrictions, or medical retirement. The career is often over.

Pro Tip for Supervisors: The “Fixing” Script

As a leader, your reaction to a report of pain determines whether your crew speaks up or shuts up. If you roll your eyes, they will hide the pain until Stage 3.

Use this script during your next toolbox talk to set the standard:

“I need you guys to be honest with me. I don’t want to hear about your back when you can’t walk anymore—at that point, it’s too late.

I want to hear about it when the tool handle feels uncomfortable or the reach is just a little too far.

Why? Because we can fix a station. We can buy a step stool. We can weld a handle extension. We can fix the job, but we can’t fix your spine.“

Practical Discussion Points for the Crew

When you gather the team for this toolbox talk, do not just read off a sheet of paper. I have seen hundreds of toolbox talks where the supervisor reads a script while the crew stares at their boots. That is a waste of time.

You need to turn the talk into an investigation. Use these specific questions to trigger real engagement and find out where the risks actually are on your site today:

“Who here has a task where they have to twist their back while holding something heavy?”

- Why ask this: You are hunting for the “Death Twist.” If a worker raises their hand (e.g., “Yeah, unloading the cement bags”), you have identified an immediate risk. Discuss moving the pallet closer or rotating the feet.

“Are there any tools we use that vibrate so much your hands feel numb after using them?”

- Why ask this: Numbness is the first stage of Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS) or “White Finger.” If a Hilti gun or a jackhammer is causing numbness, you need to check the vibration dampeners or limit the trigger time per worker.

“Is anyone reaching above their shoulders more than 10 times an hour? Can we get a step platform?”

- Why ask this: This empowers the crew to ask for equipment. Often, workers stretch because they don’t want to “waste time” fetching a ladder. Make it clear that getting the platform is part of the job, not a delay.

Field Demonstration: The “Air Lift”

Words are easily forgotten; visuals stick. Don’t just talk—show.

- Select a Volunteer: Pick a crew member to help you.

- The “Bad” Lift: Ask them to demonstrate how not to lift (simulate picking up a box from the floor with straight legs and a rounded back). Do not use real weight.

- Point out: “Look at the curve in his spine. That is where the disc pops.”

- The Correction: Ask them to step into the load, bend the knees, and bring the imaginary box into the Power Zone (chest height) before standing.

- The Comparison: Ask the group to verify: “Is his back straight? Is the load close?”

The Takeaway: “If you are lifting like the first example, you are relying on luck. If you lift like the second, you are relying on mechanics. Mechanics don’t fail; luck does.”

Conclusion

I’ve signed off on too many medical retirements for men and women under 40 because they ignored the warning signs of ergonomic stress. Ergonomics isn’t about pillows and office chairs; it’s about biomechanical survival in a harsh environment.

When you go back to work today, look at your task. If you are fighting your body to get the job done, stop. Re-assess the height, the weight, or the tool. Your job provides for your family, but your body is the only vehicle you have to enjoy that life. Protect it.