I have reviewed hundreds of accident investigation reports, and a recurring theme is the “normalization of deviance.” This occurs when a procedure is technically in place, but the workforce slowly drifts away from the strict application of it until a failure occurs. A procedure is not just a document to satisfy an ISO auditor; it is a rigid operational algorithm designed to control chaos.

In this detailed guide, I will break down the mechanics of the ten most critical OHS procedures. For each, I will outline not just the theoretical steps, but the practical execution and the common pitfalls I encounter during site inspections and audits.

TL;DR

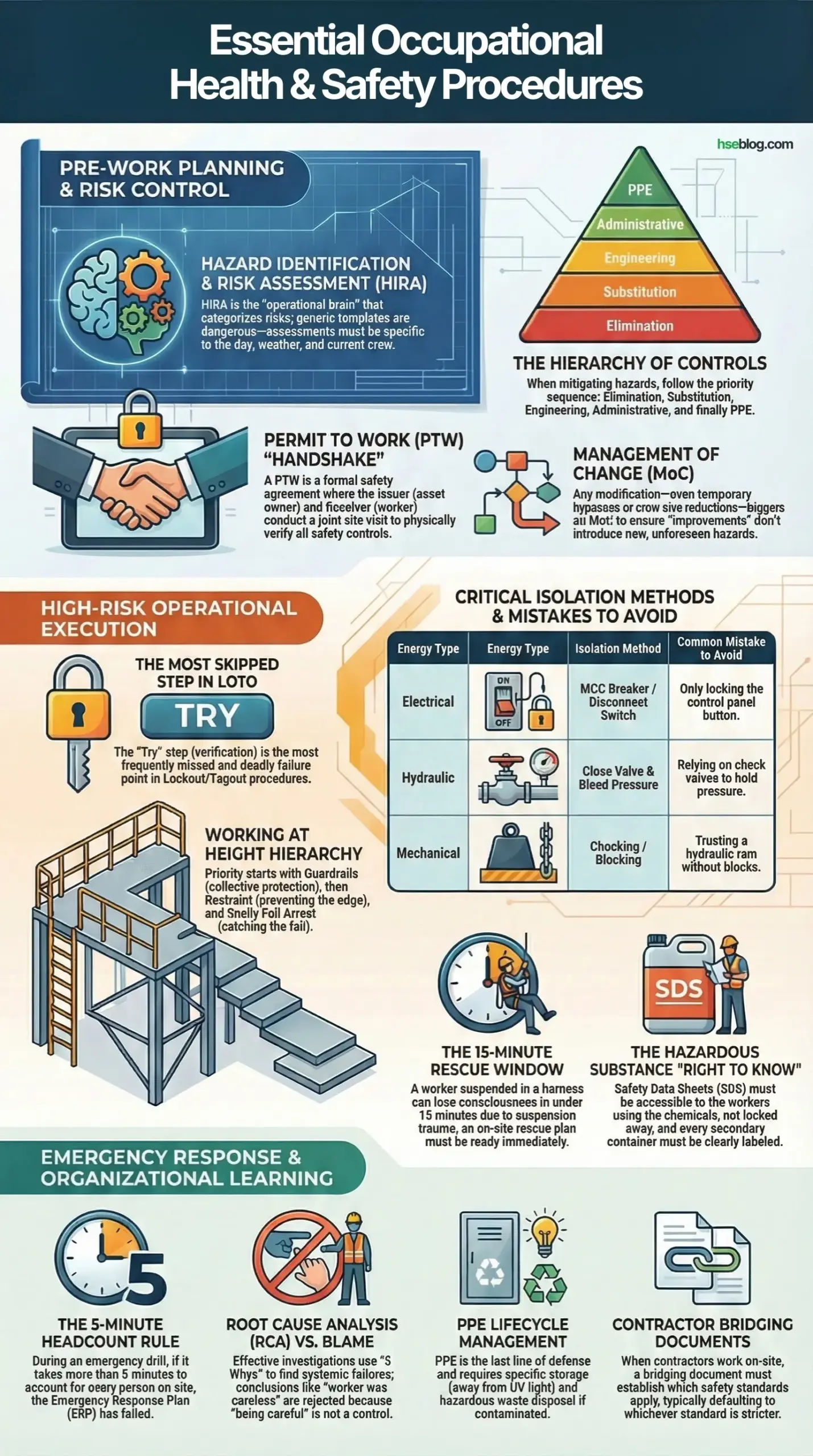

- Risk Assessments (HIRA): Must be specific to the day, weather, and crew—generic templates kill.

- Permit to Work (PTW): The signature is the least important part; the joint site inspection is what matters.

- LOTO: The “Try” step (verification) is the most skipped and the most deadly failure point.

- Change Management (MoC): Even “temporary” bypasses require full engineering and safety review.

- Rescue Plans: For work at height or confined spaces, if you can’t get them out, don’t send them in.

1. Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (HIRA)

This procedure is the operational brain of the safety system. It categorizes risks into low, medium, or high and assigns specific controls to lower that risk to As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP).

The Operational Process

- Identification: Spotting the hazard (e.g., “Working on a roof”).

- Risk Analysis: Determining likelihood and severity (e.g., “High likelihood of slip, Fatal severity”).

- Control Implementation: Applying the Hierarchy of Controls (Elimination $\rightarrow$ Substitution $\rightarrow$ Engineering $\rightarrow$ Admin $\rightarrow$ PPE).

- Review: Re-assessing if the controls actually work.

Common Field Failures

- The “Copy-Paste” JSA: Crews often copy the previous day’s Job Safety Analysis without checking if conditions changed (e.g., wind speed increased, ground is now muddy).

- Ignoring Health Hazards: We focus on safety (trauma) but often miss health risks like noise, silica dust, or vibration.

Pro Tip: I require supervisors to write the names of the specific crew members on the JSA. If the crew changes mid-shift, the JSA must be re-briefed and re-signed.

2. Permit to Work (PTW) System

The PTW is a formal handshake between the asset owner (Issuer) and the work party (Receiver). It confirms that the environment is safe enough for the work to proceed.

The Operational Process

- Application: The Receiver describes the exact scope, tools, and duration.

- Preparation: The Issuer isolates energy, drains lines, or purges gases.

- Joint Site Visit: Both parties walk the line to physically verify controls.

- Issuance: The permit is signed and posted at the job site.

- Closure: The work is done, tools are removed, and the permit is closed out.

Critical Components

- Gas Testing: Essential for Hot Work and Confined Space permits.

- Countersigning: If high-risk work crosses shifts, the incoming supervisor must re-verify the permit.

3. Lockout / Tagout (LOTO)

LOTO is the physical restraint of hazardous energy. It ensures a machine cannot move or energize while a human is inside it.

The Seven-Step Procedure

- Notify: Tell affected operators the machine is shutting down.

- Shut Down: Follow the standard stopping procedure.

- Isolate: Open breakers, close valves, disconnect lines.

- Lock and Tag: Apply a personal lock (with a unique key) and a tag with the worker’s name/photo.

- Dissipate: Bleed off residual pressure (hydraulic/pneumatic) or discharge capacitors.

- Verify (“Try”): Attempt to start the machine to prove isolation.

- Conduct Work.

Energy Type | Isolation Method | Common Mistake |

|---|---|---|

Electrical | MCC Breaker / Disconnect Switch | Locking the control panel button (not an isolation point). |

Hydraulic | Close Valve / Bleed Pressure | Relying on check valves holding pressure. |

Mechanical | Chocking / Blocking | Trusting a hydraulic ram to hold a load without blocks. |

4. Incident Reporting and Investigation

This procedure transitions an organization from “reactive” to “proactive.” It is about capturing data to prevent recurrence.

The Investigation Flow

- Immediate Action: Secure the scene, provide first aid, and preserve evidence.

- Notification: Inform management and regulators (if required).

- Fact Finding: Interview witnesses separately; gather photos, CCTV, and logs.

- Root Cause Analysis (RCA): Use tools like “5 Whys” or Fishbone diagrams to find the systemic failure.

- Corrective Actions: Implement changes to prevent the root cause, not just the symptom.

Cultural Insight

If I see an incident report that concludes with “Worker cautioned to be more careful,” I reject it. “Be careful” is not a control measure. The investigation must answer why the system allowed the error to happen.

5. Emergency Response Plan (ERP)

The ERP dictates the command and control structure during a crisis. It replaces panic with protocol.

Key Elements

- Evacuation Routes & Assembly Points: These must be clear, lit, and unobstructed.

- Emergency Communications: How do we talk if radios fail? Who calls the ambulance?

- Specialized Response: Specific protocols for chemical spills (HAZMAT), fire, or confined space rescue.

Field Reality: During drills, I watch the “headcount” process. If it takes more than 5 minutes to account for everyone, the procedure has failed. In a real fire, those minutes are the difference between rescue and recovery.

6. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Management

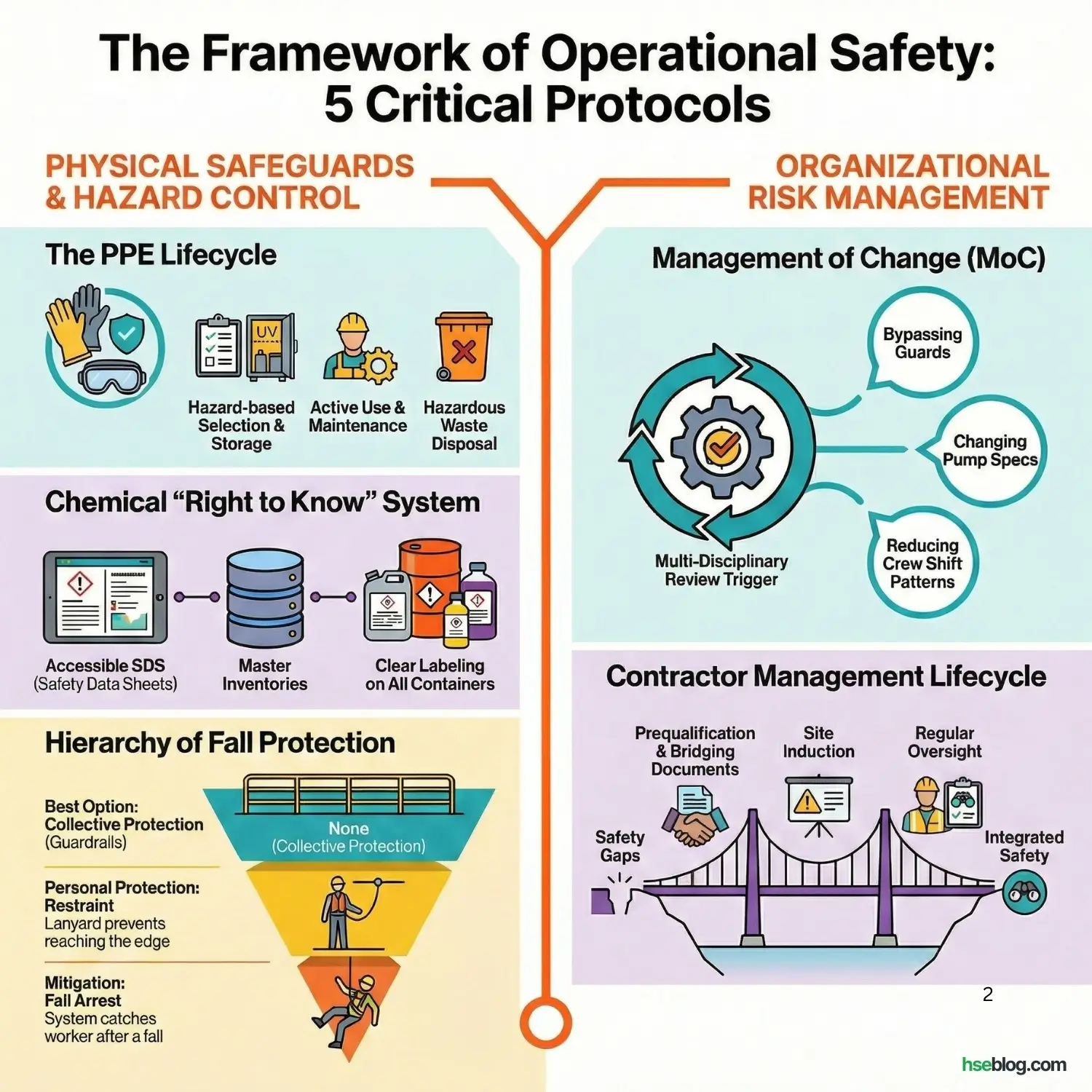

This procedure ensures that the “last line of defense” is functional. It covers the entire lifecycle of the equipment.

Detailed Requirements

- Selection: Based on specific hazard exposure (e.g., Cut Level 5 gloves for handling sheet metal vs. Cut Level 1 for general handling).

- Storage: UV light degrades plastics (helmets) and synthetic fibers (harnesses). PPE must be stored in cool, dark places.

- Disposal: Contaminated PPE (oil, chemicals) is hazardous waste and must be disposed of accordingly.

7. Management of Change (MoC)

MoC is the gatekeeper for modification. It prevents “improvement” from becoming an “incident.”

When MoC is Triggered

- Equipment Changes: Bypassing a safety guard, changing a pump spec, installing a temporary hose.

- Process Changes: Increasing temperature/pressure beyond design limits.

- Personnel Changes: Reducing crew size or changing shift patterns.

The Review Process

A multi-disciplinary team (Engineering, HSE, Operations) reviews the proposed change to ask: “Does this introduce new hazards?” If yes, those hazards must be mitigated before the change is approved.

8. Contractor Management

This procedure bridges the gap between the host company’s standards and the contractor’s capabilities.

The Lifecycle

- Prequalification: Checking the contractor’s safety stats (TRIR/LTIR) before bidding.

- Bridging Document: A formal agreement on whose procedures apply (Host vs. Contractor). Usually, the stricter standard wins.

- Induction: Training contractor staff on site-specific hazards.

- Oversight: Regular audits to ensure they aren’t cutting corners to meet deadlines.

9. Hazardous Substances (COSHH / HazCom)

This procedure manages the chemical risks on site, ensuring workers know what they are handling.

The “Right to Know” System

- Inventory: A master list of every chemical on site.

- Safety Data Sheets (SDS): Must be accessible (paper or digital) to the workers using the chemical, not locked in an office.

- Labeling: Every container, including secondary bottles (like spray bottles), must have a label identifying the contents and the primary hazard (e.g., Flammable, Corrosive).

10. Working at Height

This procedure applies to any work where a fall can cause injury. It is strictly governed because gravity has a 100% success rate.

Hierarchy of Controls for Height

- Guardrails (Collective Protection): The best option because it requires no action from the worker.

- Restraint (Personal Protection): A lanyard short enough that the worker physically cannot reach the edge.

- Fall Arrest (Mitigation): A system that catches the worker after they fall.

The Rescue Plan

This is the most critical part of the procedure. A worker suspended in a harness can lose consciousness in under 15 minutes due to suspension trauma (blood pooling in legs). The procedure must include:

- On-site rescue equipment (ladder, lift, descent device).

- Trained rescue personnel (Do not rely on calling the fire department; they may be too far away).

Conclusion

Understanding these procedures “in detail” means understanding their intent. We don’t do LOTO to annoy the electricians; we do it to ensure they go home to their families. We don’t do MoC to slow down engineering; we do it to prevent explosions.

As a practitioner, your goal is to master the execution of these procedures. A procedure that lives only in a manual is a liability. It must be taught, drilled, and enforced on the shop floor every single day.