I once walked onto a Tier-1 petrochemical expansion project and stopped a crew of pipefitters working on a pipe rack 12 meters up. They had their harnesses on, but they were clipped to a 2-inch conduit—a “perceived” anchor point that would have snapped like a twig in a fall. This is the reality of work at height: it’s not just about having the gear; it’s about the life-and-death physics of how that gear is applied in a high-pressure environment.

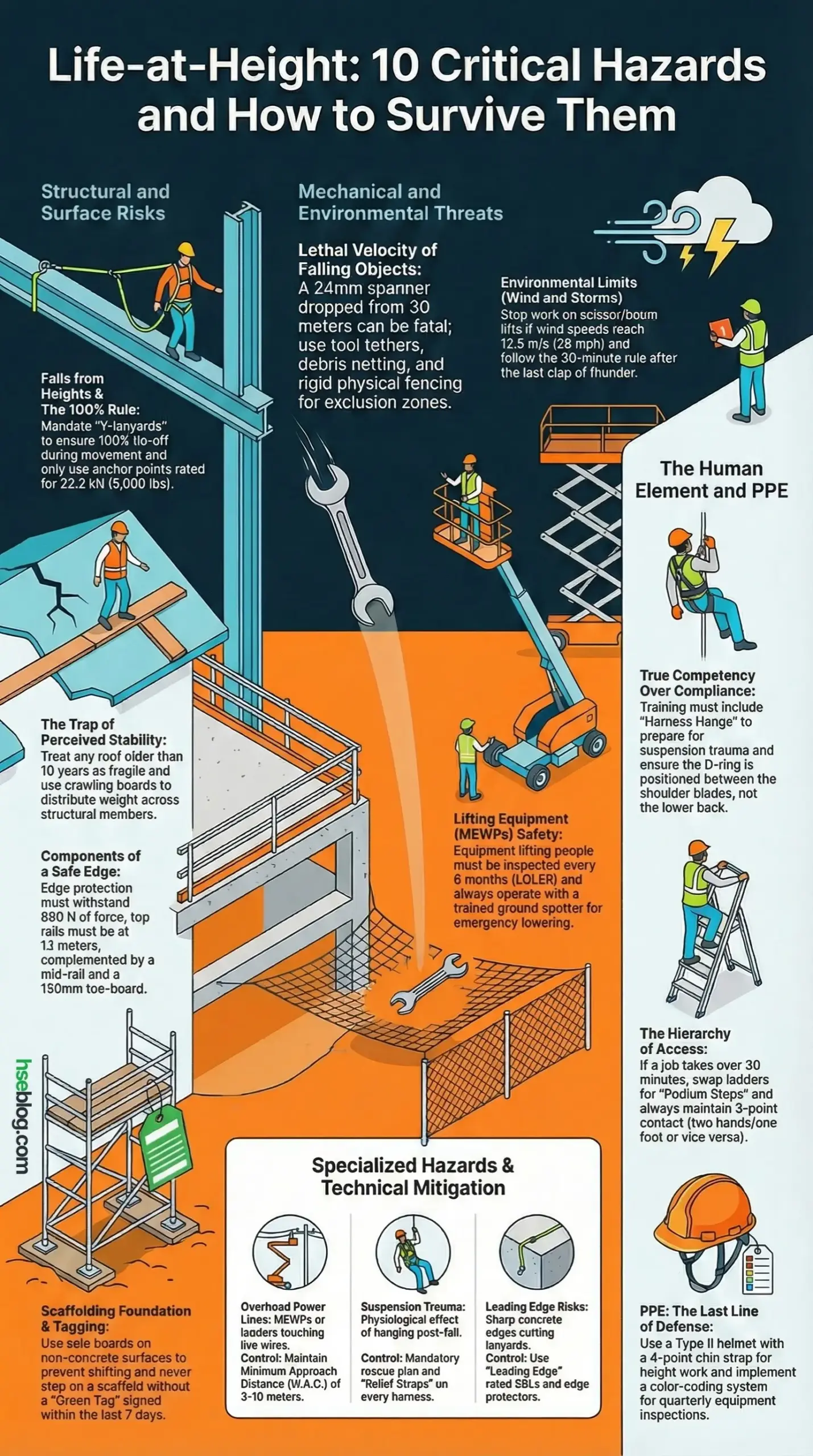

Falls from height remain the leading cause of workplace fatalities globally. This article breaks down the 10 most critical hazards encountered on-site and provides the field-tested control measures required to ensure every worker who goes up comes back down safely. We will cover technical failures, environmental triggers, and the human errors that bypass even the best safety systems.

TL;DR

- The 100% Rule: Any work above 1.8 meters (or where a fall could cause injury) requires a formal permit and 100% tie-off.

- Inspect Before Use: Never trust a pre-erected scaffold or a harness without a personal pre-use check; tags can be faked or outdated.

- The Drop Zone: Falling objects are as lethal as falling people; use toe-boards, tool tethers, and exclusion zones religiously.

- Competency Over Compliance: A harness is a death trap if the wearer doesn’t know how to fit it or lack a rescue plan for suspension trauma.

Comprehensive Analysis of Working at Height Hazards

Safety at height requires more than just wearing a harness; it demands a systematic identification of physical, mechanical, and environmental threats. Lets breakdown of the ten most critical hazards found in complex operational environments, along with the field-tested controls necessary to mitigate them.

1. Falls from Heights

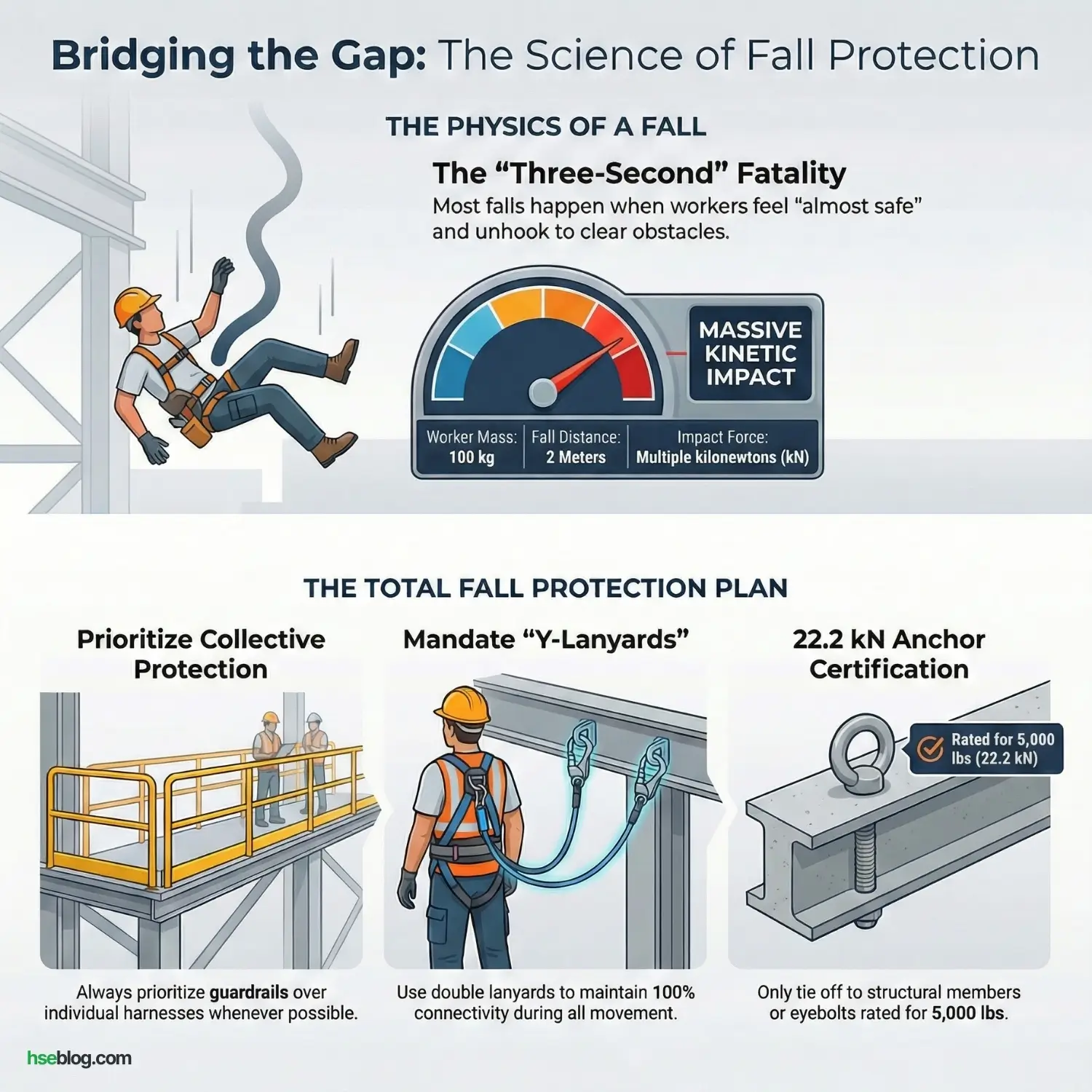

In my decade on-site, I’ve realized that the most dangerous distance isn’t the drop itself—it’s the gap in your safety system. Workers often fall when they feel “almost safe,” such as stepping from a ladder onto a platform. They unhook their lanyard to clear a strut, and in those three seconds, a slip becomes a fatality.

The Physics of the Fall

When a worker falls, the forces involved are massive. If you weigh 100kg and fall just 2 meters, you are hitting the end of that lanyard with a force equivalent to several kilonewtons.

- Control Measure: Implement a “Total Fall Protection” plan. Prioritize collective protection (guardrails) over individual protection (harnesses).

- Double Lanyards: Mandate “Y-lanyards” so workers can maintain at least one connection point at all times during movement.

- Anchor Point Certification: I’ve seen people tie off to handrails or small pipes. Only use structural members or certified eyebolts rated for $22.2 \text{ kN}$ ($5,000 \text{ lbs}$).

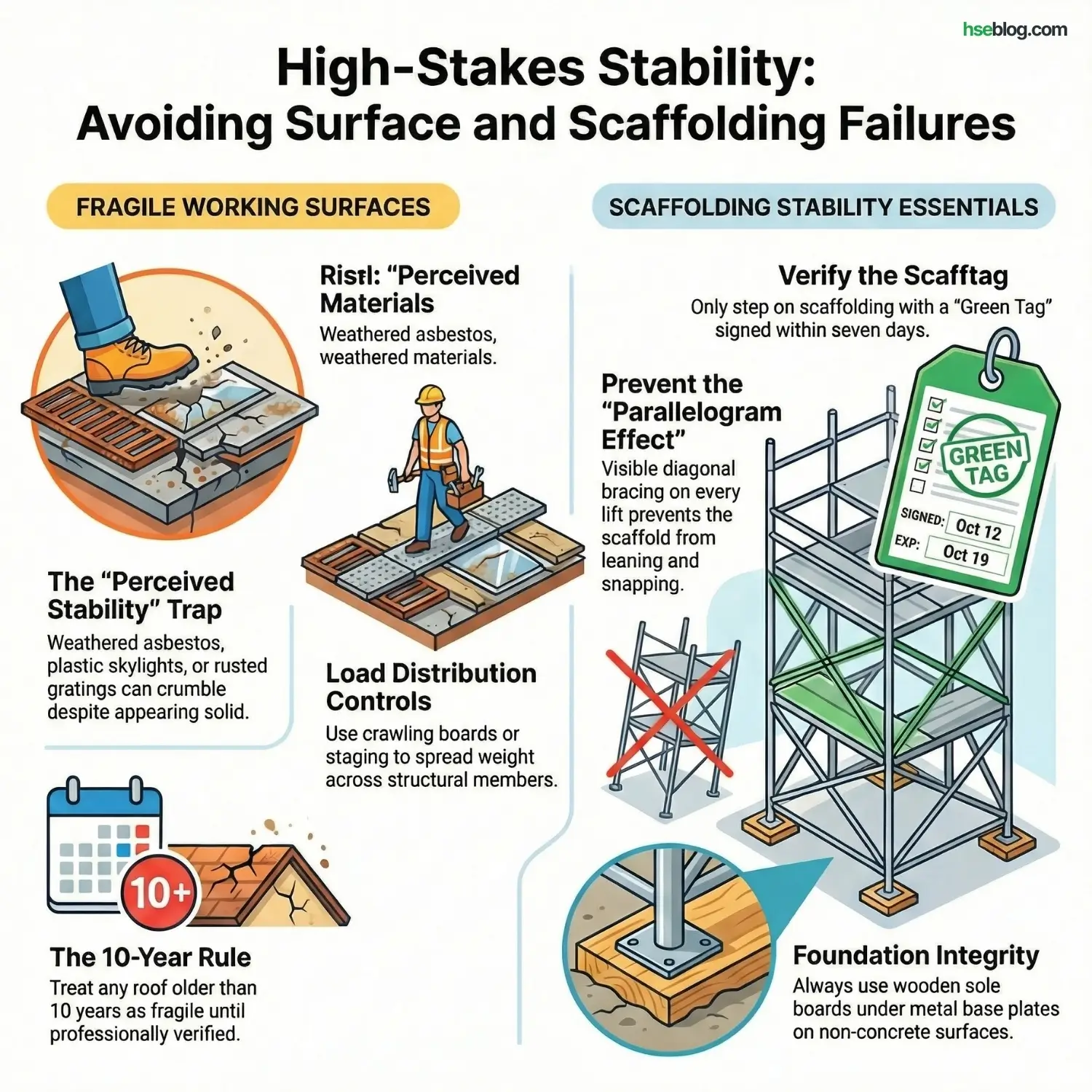

2. Unstable Working Surfaces

I’ve walked onto roofs where the asbestos cement or plastic skylights were so weathered they would crumble under the weight of a hammer, let alone a man. The hazard here is “perceived stability”—the surface looks solid, but its structural integrity is gone.

Identifying the Trap

Surface hazards include rusted floor gratings in chemical plants (corrosion eats the underside first) and un-sheeted roof purlins.

- Control Measure: Use crawling boards or “staging” to spread the load across structural members.

- The “Two-Man” Rule: Never allow a worker on a potentially fragile surface alone.

- Pro Tip: Always treat any roof older than 10 years as “fragile” until a structural engineer or competent supervisor proves otherwise.

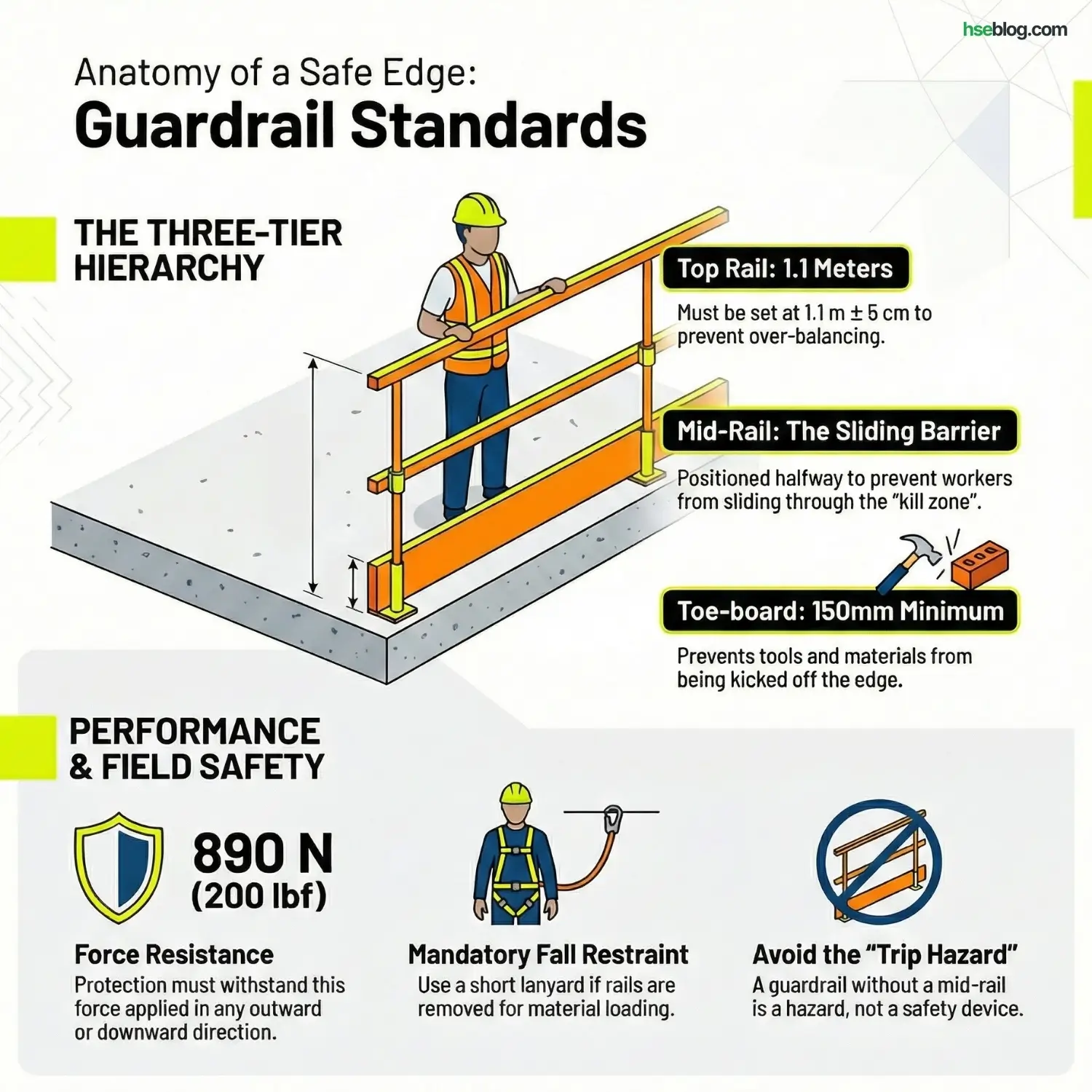

3. Inadequate Edge Protection

A guardrail without a mid-rail is just a trip hazard. During a bridge deck inspection, I found sections where the mid-rail was removed to pass materials through. This creates a “kill zone” where a worker could easily slide under the top rail if they tripped.

Components of a Safe Edge

Edge protection must withstand a force of at least $890 \text{ N}$ ($200 \text{ lbf}$) applied in any outward or downward direction.

- The Hierarchy: 1. Top Rail: Must be at $1.1 \text{ meters} \pm 5 \text{ cm}$ to prevent over-balancing.2. Mid-Rail: Positioned halfway to stop anyone from sliding through.3. Toe-board: Minimum 150mm high to stop tools from being kicked off.

- Field Insight: If you must remove a rail for loading, the worker must be in a “Fall Restraint” system (a short lanyard that physically prevents them from reaching the edge).

4. Falling Objects (Drops)

Gravity works both ways. I’ve investigated “near-misses” where a 24mm spanner fell 30 meters and embedded itself in a wooden pallet. If that had hit a worker, no hard hat in the world would have saved them.

Securing the Vertical Plane

The hazard isn’t just the object; it’s the lack of communication between the “top-side” and “ground-side.”

- Control Measure: Use tool tethers (lanyards for tools). If it’s not tied to you, it shouldn’t be in your hand at height.

- Debris Netting: Wrap the outside of scaffolds in fire-rated netting to catch smaller debris.

- Exclusion Zones: Use rigid barriers. I’ve seen workers walk right through “caution tape” because they were looking at their phones. Use physical fencing.

5. Scaffolding Collapse

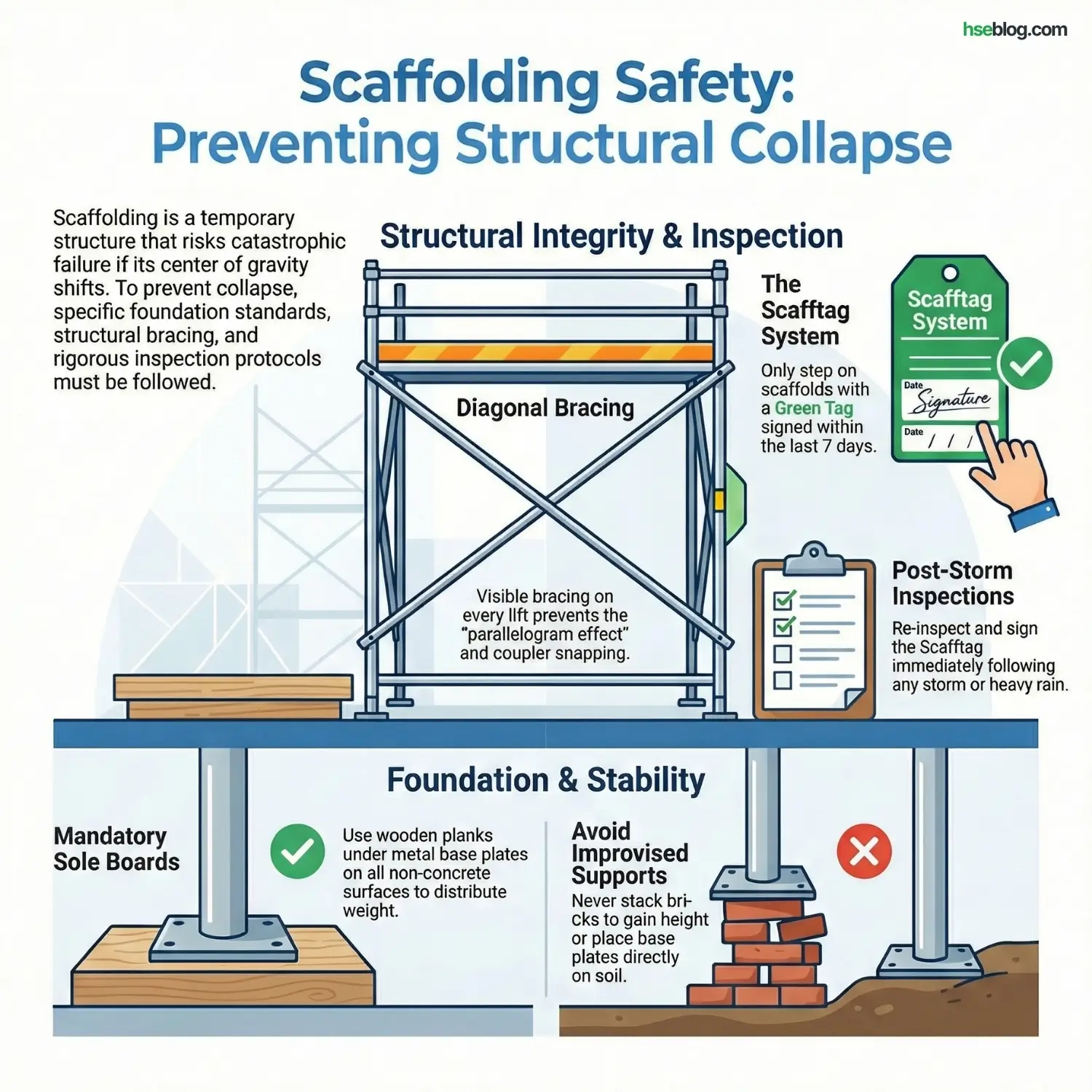

A scaffold is a temporary building. When I see base plates sitting directly on soil or “stacked” on bricks to gain height, I see a catastrophe waiting to happen. If the ground shifts due to rain or vibration, the whole structure loses its center of gravity.

Foundation and Bracing

Technical Check: Ensure “diagonal bracing” is visible on every lift. This prevents the “parallelogram effect” where the scaffold leans and eventually snaps its couplers.

Sole Boards: These are the wooden planks under the metal base plates. They must be used on any surface that isn’t solid concrete to distribute the load.

Scafftag System: Never step on a scaffold that doesn’t have a “Green Tag” signed within the last 7 days (or after a storm).

6. Failure of Lifting Equipment

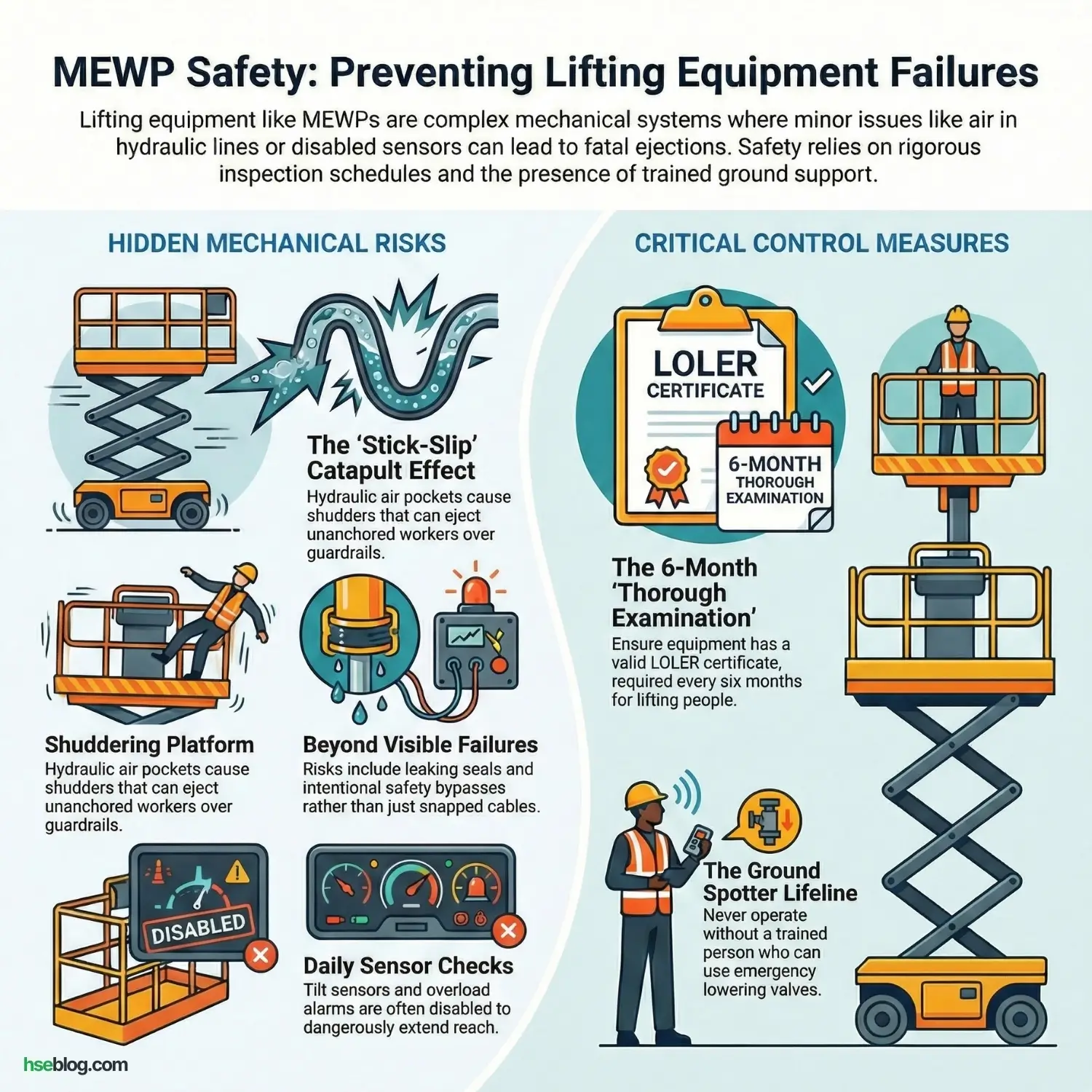

In the field, I’ve seen Mobile Elevated Work Platforms (MEWPs) “shudder” due to air in the hydraulic lines—a phenomenon called stick-slip. If a worker isn’t anchored inside that basket, that sudden jolt can literally catapult them over the guardrail. Lifting equipment is a complex mechanical system that requires rigorous oversight.

Beyond the Controls

Mechanical failure isn’t always a snapped cable; it’s often a safety bypass or a leaking seal.

- Control Measure: Check the “Thorough Examination” certificate. Under regulations like LOLER, any equipment lifting people must be inspected every 6 months.

- The Ground Spotter: Never allow a MEWP to operate without a trained ground person who knows how to use the emergency lowering valves. If the operator faints or the basket loses power, that spotter is the only lifeline.

- Pro Tip: Inspect the “tilt sensor” and “overload alarm” daily. I’ve caught crews trying to disable these to reach “just a bit further.”

7. Poor Weather Conditions

I once had to evacuate a cooling tower project because a sudden storm brought 50 km/h gusts. The “sail area” of a person or a piece of plywood at height is significant. Wind doesn’t just push you; it creates instability that leads to panic and mistakes.

Environmental Limits

Rain makes steel gratings slippery, and lightning makes every crane a lightning rod.

- Control Measure: Use a handheld or mounted anemometer. Don’t guess the wind speed. For most scissor lifts and booms, the cut-off is 12.5 m/s (approx. 28 mph).

- The 30-Minute Rule: If you hear thunder, stop work. Do not resume until 30 minutes after the last clap of thunder.

- Action: In winter, “Ice Fall” from upper structures is a major hazard for those working below. Clear all ice from platforms before the shift starts.

8. Lack of Training

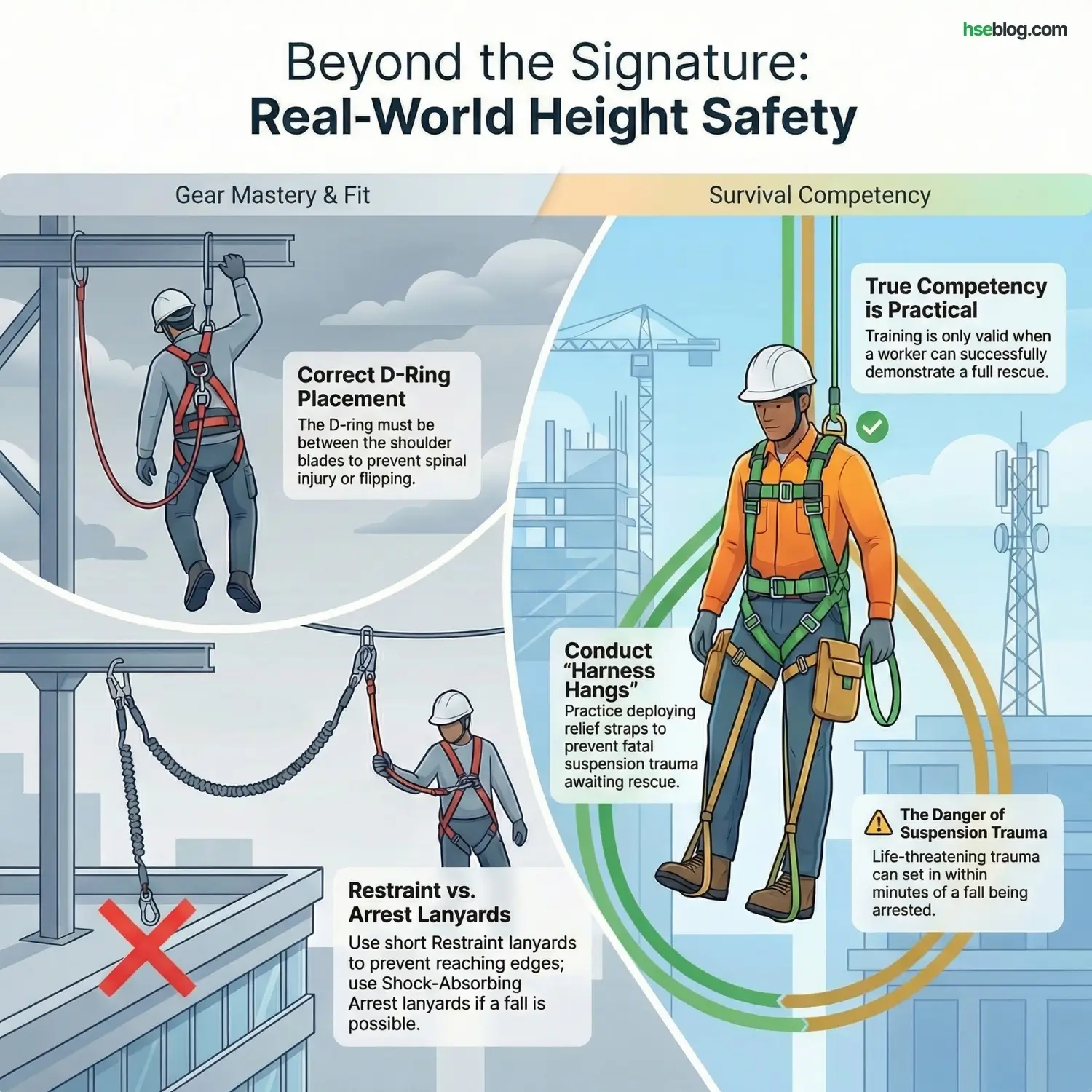

I’ve walked up to workers who were wearing high-end harnesses, only to find their “D-ring” was positioned at the small of their back instead of between the shoulder blades. If they fell, the harness would likely snap their spine or cause them to flip upside down.

True Competency

Working at Height Training isn’t a signature on a sheet; it’s the ability to demonstrate a rescue.

- Control Measure: Conduct “Harness Hangs.” Suspension trauma can set in within minutes. If a worker doesn’t know how to deploy their “relief straps” while hanging, they are at risk of death even after the fall is arrested.

- Differentiation: Ensure workers know that a Fall Restraint lanyard (short, fixed length) is used to prevent reaching an edge, while a Fall Arrest lanyard (with a shock absorber) is for when a fall is possible.

9. Improper Use of Equipment

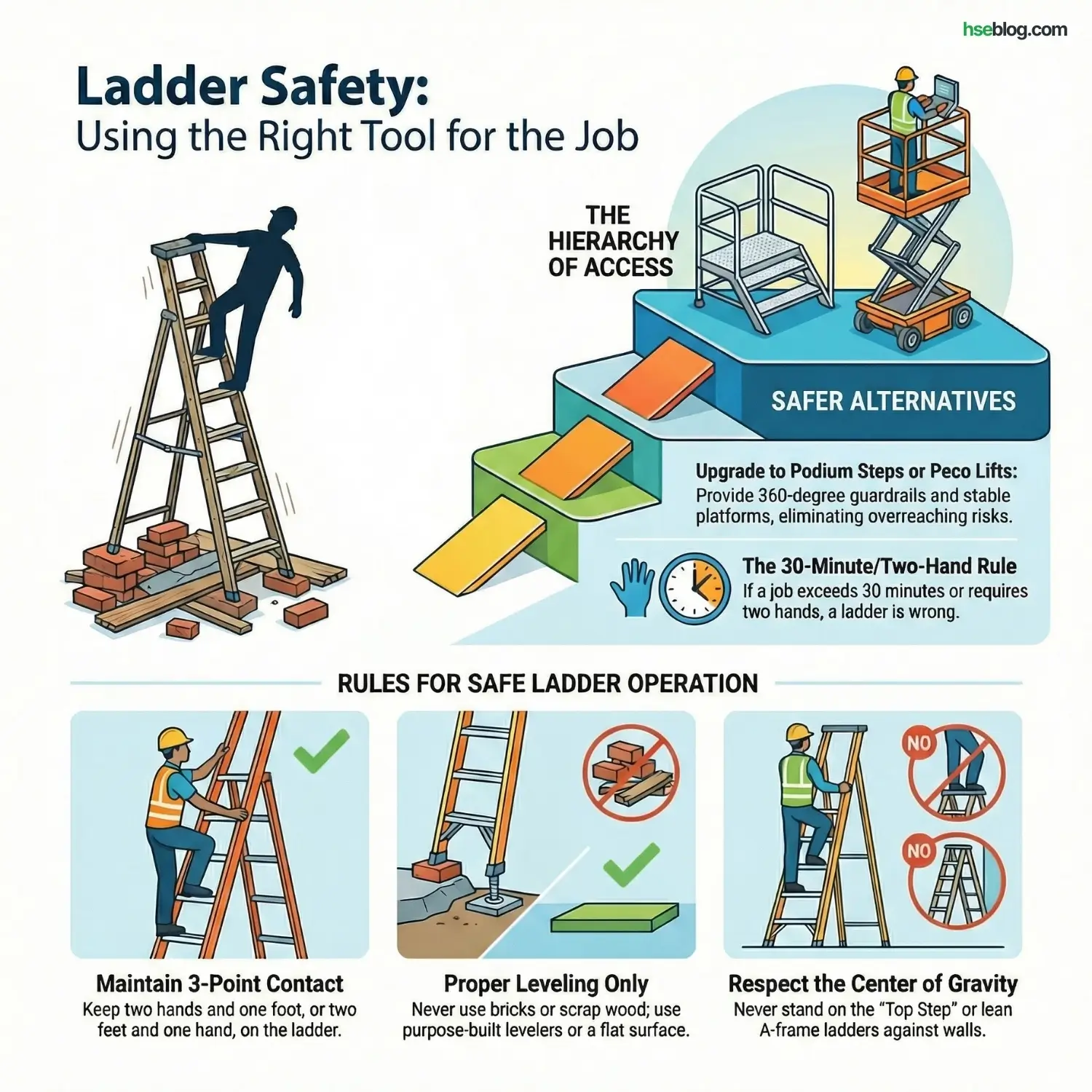

The ladder is the most abused tool on any job site. I frequently see workers standing on the “Top Step” of an A-frame or leaning a step-ladder against a wall. These tools are designed for specific forces; using them improperly changes their center of gravity instantly.

The Hierarchy of Access

If a job takes longer than 30 minutes or requires two hands, a ladder is the wrong tool.

- Control Measure: Enforce the 3-Point Contact rule: two hands and one foot, or two feet and one hand on the ladder at all times.

- Leveling: Never use bricks or scrap wood to level a ladder. Use purpose-built ladder levelers or move the ladder to a flat surface.

- Selection: Swap ladders for “Podium Steps” or “Peco Lifts.” They provide a 360-degree guardrail and a stable platform, eliminating the risk of overreaching.

10. Lack of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

PPE is often called the “Last Line of Defense” because it only works after every other safety measure (guardrails, permits, training) has failed. If your harness is sitting in the back of the truck, your plan B doesn’t exist.

Quality and Inspection

I’ve seen lanyards used near welding sparks that were half-burned through. That lanyard is now a piece of string.

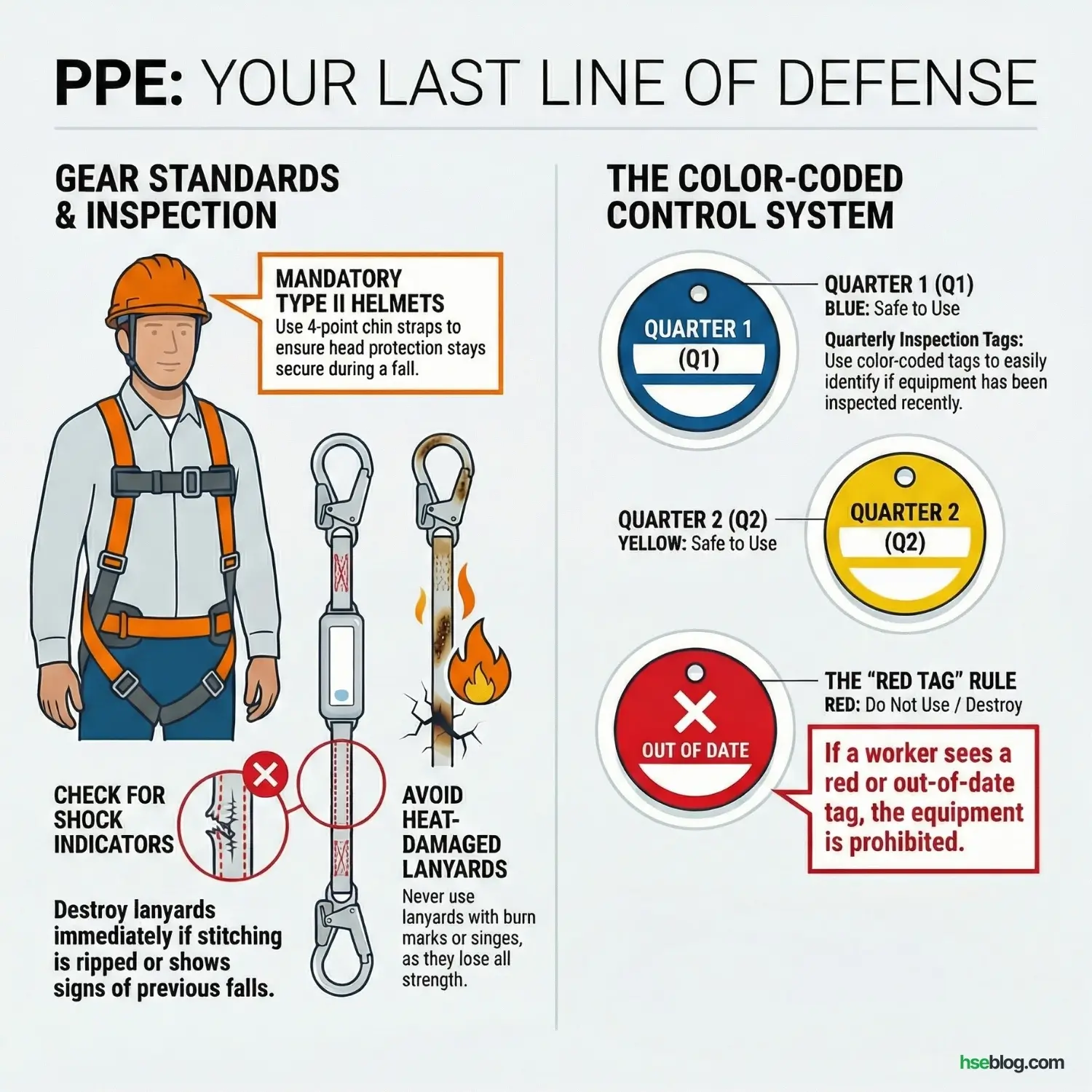

- Control Measure: Implement a Color-Coding System. For example, a blue tag means it was inspected in Q1, a yellow tag for Q2. If a worker sees a “Red” or “Out of Date” tag, they shouldn’t use it.

- The Chin Strap: Standard hard hats fall off the moment you look up or down. For work at height, a Type II helmet with a 4-point chin strap is mandatory to ensure the head stays protected during a fall.

- Inspection: Check for “shock indicators.” If the stitching on a lanyard is ripped, it has already seen a fall and must be destroyed immediately.

Additional Working At Height Hazards

| Hazard Type | Real-World Context | Control Strategy |

| Overhead Power Lines | MEWPs or ladders touching live wires. | Maintain “M.A.D.” (Minimum Approach Distance)—usually 3-10 meters. |

| Suspension Trauma | The physiological effect of hanging in a harness post-fall. | Mandatory: Have a rescue plan and “Relief Straps” on every harness. |

| Leading Edge Risks | Sharp concrete edges cutting lanyards during a fall. | Use “Leading Edge” rated SRLs and edge protectors. |

Conclusion

Working at height doesn’t have to be a gamble. In my decade on-site, I’ve learned that the most dangerous hazard isn’t the height itself—it’s the normalization of deviance, where we stop seeing the risk because “we did it this way yesterday and nobody died.”

True HSE authority isn’t found in a thick procedure manual; it’s found in the courage to stop a job when a scaffold tie is missing or a wind gust picks up. We owe it to the crews to ensure that the hierarchy of controls is lived, not just filed. Safety is a moral contract: we go up together, and we all come home together.